There Will Be Blood: Frank Castorf Has Entered the Ring

Wer helfe mir? Loge (Norbert Ernst) and Mime (Burkhard Ulrich) arguing at the petrol station in Frank Castorf's production of Das Rheingold, without question, a tour de force and quite clearly the high point of Castorf’s vision. It is set in a motel, a bar and a petrol station on the iconic Route 66.

Photo: Enrico Nawrath / Bayreuther Festspiele

As part of the 200th anniversary celebrations of Richard Wagner’s birth, Bayreuth has staged a new production of the Ring. Oil - the black gold – is the underlying theme in this bewildering production by the artistic director of Berlin's Volksbühne, Frank Castorf. Castorf, who clearly had very limited rehearsal time, takes an essentially non-Wagnerian view of the work. The result is a provocative, irritating yet fascinating production that could best be described as an 'imploded' work of art.

Das Rheingold Cast 2013

Aleksandar Denic’s magnificent scenography in each of the operas offers unlimited possibilities for vertical scenic activity. The intrigues of the gods are set against brash Western popular culture.

Photo: Enrico Nawrath / Bayreuther Festspiele

Conductor Kirill Petrenko; Director Frank Castorf;

Stage design Aleksandar Denić;

Costumes Adriana Braga Peretzki;

Lighting Rainer Casper;

Video Andreas Deinert and Jens Crull

Wotan Wolfgang Koch;

Donner Oleksandr Pushniak;

Froh Lothar Odinius;

Loge Norbert Ernst;

Fasolt Günther Groissböck;

Fafner Sorin Coliban;

Alberich Martin Winkler;

Mime Burkhard Ulrich;

Fricka Claudia Mahnke;

Freia Elisabet Strid;

Erda Nadine Weissmann;

Woglinde Mirella Hagen;

Wellgunde Julia Rutigliano;

Flosshilde Okka von der Damerau

Die Walküre Cast 2013

Conductor Kirill Petrenko; Director Frank Castorf;

Stage design Aleksandar Denić;

Costumes Adriana Braga Peretzki;

Lighting Rainer Casper;

Video Andreas Deinert and Jens Crull

Siegmund Johan Botha; Hunding Franz-Josef Selig; Wotan Wolfgang Koch; Sieglinde Anja Kampe; Brünnhilde Catherine Foster; Fricka Claudia Mahnke; Gerhilde Allison Oakes; Ortlinde Dara Hobbs; Waltraute Claudia Mahnke; Schwertleite Nadine Weissmann; Helmwige Christiane Kohl; Siegrune Julia Rutigliano; Grimgerde Geneviève King; Rossweisse Alexandra Petersamer

Siegfried Cast 2013

Conductor Kirill Petrenko; Director Frank Castorf;

Stage design Aleksandar Denić;

Costumes Adriana Braga Peretzki;

Lighting Rainer Casper;

Video Andreas Deinert and Jens Crull

Siegfried Lance Ryan; Mime Burkhard Ulrich; Der Wanderer Wolfgang Koch; Alberich Martin Winkler; Fafner Sorin Coliban; Erda Nadine Weissmann; Brünnhilde Catherine Foster; Waldvogel Mirella Hagen

Götterdämmerung Cast 2013

Conductor Kirill Petrenko; Director Frank Castorf;

Stage design Aleksandar Denić;

Costumes Adriana Braga Peretzki;

Lighting Rainer Casper;

Video Andreas Deinert and Jens Crull

Siegfried Lance Ryan; Gunther Alejandro Marco-Buhrmester; Hagen Attila Jun; Alberich Martin Winkler; Brünnhilde Catherine Foster; Gutrune Allison Oakes; Waltraute Claudia Mahnke; 1. Norn Okka von der Damerau; 2. Norn Claudia Mahnke; 3. Norn Christiane Kohl; Woglinde Mirella Hagen; Wellgunde Julia Rutigliano; Flosshilde Okka von der Damerau

Castorf’s distinctly unmusical approach to Wagner is fundamentally problematic. There are few signs, if any, that the director is able to relate to Wagner’s music, with the exception perhaps of his seemingly ironic efforts to trivialise the central scenes and climaxes. The director’s anti-heroic and anti-seduction approach throws a grey, ironic veil over the work instead of entering a dialogue with it. I remain ambivalent; the production continues to fascinate (and irritate) me long after my return to Norway.

Somewhat paradoxically, however, Castorf’s markedly unmusical approach cannot be simply ridiculed or rejected. It was a refreshing experience despite all its shortcomings. In its premiere year, there are many aspects of Castorf’s Ring which remain incomplete, especially the noticeable lack of direction. Nonetheless, there is a sense of genuine artistic expression at the heart of this production.

It should be remembered that the Boulez/Chéreau Ring began life as a disastrous scandal yet ultimately became one of Bayreuth’s greatest successes. Perhaps Castorf’s Ring will enjoy the same fate? Chéreau’s Ring also exhibited some major weaknesses in its first season. (In an interview with Die Zeit, Chéreau himself described one third of the Ring in its first season as “ganz schlecht”, Act III of Die Walküre as “furchtbar” and Act III of Siegfried as “entsetzlich”.)

Castorf is a representative of what is termed postdramatic theatre which is characterized, in part, by a rejection of traditional narrative and the classic psychological portrayal of characters, fragmentation, multi-perspective, parallel actions, and disrupted chronology. The director has expressed his dislike of linear stagings as the reason for not becoming more closely involved with opera. The director compares not being granted the “freedom to move a storyline through time and space the way I want” with working “for the railway system and … [making] … sure the trains run on time”.

Juxtaposing elements similar to the montage technique in film is how Castorf would have preferred to stage Wagner's Ring. He was, however, not allowed to chop up the score, change the order of the scenes and insert other elements. Montage from Sergei Eisenstein's film Battleship Potemkin (1925) - "Odessa Steps" sequence.

“Cinema is, first and foremost, montage”, wrote Soviet film director and theorist Sergei Eisenstein in 1929. And montage is what Castorf would have preferred to use in this production. In other words, the director of the bicentennial Ring has undertaken the task despite not being allowed to do what lies at the core of his artistic project.

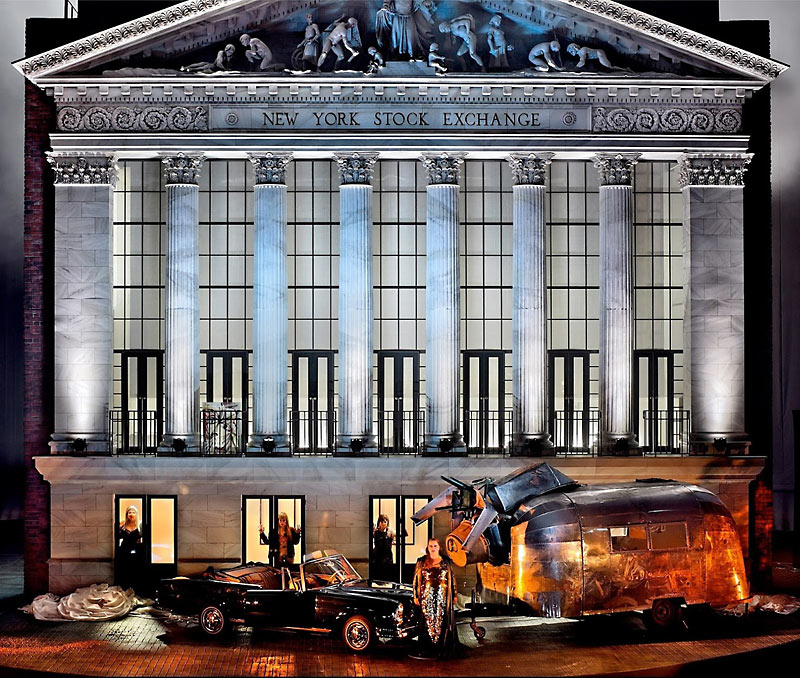

The Rhine Daugthers and Brünnhilde outside the Stock Exchange on Wall Street. Götterdämmerung. During “Starke Scheite” one of the Rhinedaughters carries a painting (Picasso?) out of the Stock Exchange building. Should we read this as a manifesto that art must free itself from commerce?

Photo: Enrico Nawrath / Bayreuther Festspiele

It is apparent that the grand Wagnerian pathos is foreign to the director, and his concept works against rather than with the intentions of the composer. Castorf seems to find some sort of connection between the absurdity of the media dominated world of the West and Wagner’s seductive universe. A major task for the director seems to be the desire to strip Wagner bare. The audience will not be permitted to sink unbewusst, höchste Lust into Wagner’s seductive aesthetic of grand emotions, nor enjoy the uncritical adulation of heroes, nor identify with the “tragedy” of the gods. Everything that is sublime is trivialised. The villains (the gods and Siegfried, according to Castorf) are deprived of depth and tragic dimension. We are bombarded with a form of anti-action accompanied by seemingly irrelevant parallel events (mostly on video), anachronisms, and the introduction of diverse supporting actors not detailed in the score (namely, a bartender, a slave, two crocodiles, two cameramen, and revolutionary freedom fighting heroes, etc.).

Sorin Coliban (Fafner) and Günther Groissböck (Fasolt), Photo: Enrico Nawrath / Bayreuther Festspiele

The rejection of basic dramaturgical principles are more the rule than the exception. All of this is packed into a form of intensely physical theatre where mattresses and chairs are tossed wildly around and water is sprayed all over. Mustard, blood and oil are smeared over the singers’ faces and stomachs. Ohne Kunst wie im Kinderspiel. I believe I was not the only one in the Festspielhaus feeling I was trapped in a kindergarten. Such nuance that does exist is mostly overwhelmed by the infantile behaviour. The intentional logical flaws in the dramaturgy (such as Fafner leaving behind the gold after killing Fasolt, and Mime and Alberich being captured by Wotan, and Loge already on the descent to Nibelheim) bewildered the Bayreuth audience.

Das Rheingold - a tour de force and quite clearly the high point of Castorf’s vision: The excellent cast outside the motel on the revolving stage: Claudia Mahnke (Fricka), Wolfgang Koch (Wotan), Norbert Ernst (Loge), Sorin Coliban (Fafner), Günther Groissböck (Fasolt), Oleksandr Pushniak (Donner), Lothar Odinius (Froh) and Elisabet Strid (Freia). Photo: Enrico Nawrath / Bayreuther Festspiele

Das Rheingold, without question, is a tour de force and quite clearly the high point of Castorf’s vision. It is set in a motel, a bar and a petrol station on the iconic Route 66 – immortalised in John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath (later filmed by John Ford). Wagner’s mythological creatures are supplanted by pimps, whores and Mafia figures. The entire drama is presented as a crime film. The audience is treated to a fantastic firework of ideas brilliantly executed, with excellent timing, superb direction and a fascinating multiple perspective. This is intelligently conveyed in the stage design of Aleksander Denic, and is indeed one of the finest I have ever seen on the opera stage. The use of video filming in real time works on different levels, from the voyeuristic documentarism of modern media and our narcissistic culture. The often abusive nature of journalism is emphasized more clearly in Götterdämmerung by the intruding cameramen.

Waldvogel, maybe representing the hollow, narcissistic entertainment culture of the Western world. A parody of the aesthetics of seduction, and consequently of the whole Wagnerian enterprise?

Photo: Enrico Nawrath / Bayreuther Festspiele

Aleksandar Denic’s magnificent scenography in each of the operas (see photos) offers unlimited possibilities for vertical scenic activity. The revolving stage over two or three floors is used to maximum effect, opening new rooms and perspectives (also thanks to the constant video filming), and the opportunities are constantly adapted to the production’s universe. The Assistant Director, Patric Seibert, helps to tie the scenes together. He appears in Das Rheingold, Siegfried and Götterdämmerung as a bartender, waiter, Mafia victim, and the owner of a kebab takeaway.

Das Rheingold calls to mind The Sopranos, Pulp Fiction and the surreal universes of David Lynch. The intrigues of the gods are set against brash Western popular culture. The film concept is present throughout, but Castorf consciously violates dramatic logic and structure. This is playful, hyper-realistic, anti-realistic absurd theatre. We are constantly reminded that this is fiction. And so are the characters; they are trapped in a Pirandello-esque stage prison. They are trapped in reality, and reality is fiction. They try to find ways out of the scene, only to discover that they are dead ends. There is no escape. The slave to Siegfried and Mime (a variant of The Gimp in Pulp Fiction) reads studiously, perhaps questioning whether he can escape from his prison (he is also a slave of the TV), or if there is any hope at all.

One of the magnificent stage designs for Die Walküre by Aleksandar Denić, probably inspired by Paul Thomas Anderson's film There Will Be Blood about a prospector in the early days of the oil business. Anja Kampe (Sieglinde), Johan Botha (Siegmund) and Franz-Josef Selig (Hunding) form a vocally strong triangle, but the Personenregie - oh god! can it get worse? And how absurd is it to cast Johan Botha in a Castorf production!? Photo: Enrico Nawrath / Bayreuther Festspiele

After Das Rheingold quality standards drops dramatically and it is here that the artistic team will face a major challenge in the years to come. The lack of direction in Die Walküre, is particularly evident. Only video close-ups of the Valkyries are able to rescue the production from collapsing totally. Musically, however, Die Walküre is of the highest order, with Johan Botha (Siegmund) and Anja Kampe (Sieglinde) at the head of an outstanding ensemble.

Wolfgang Koch (Wotan) - the ending of Die Walküre.

Photo: Enrico Nawrath / Bayreuther Festspiele

Siegfried sits on the asphalt, leaning against a lamppost while he sings “Doch ich bin so allein, hab’ nicht Brüder noch Schwestern: meine Mutter schwand, mein Vater fiel ...” (Siegfried,Act II). It is a potent image of loneliness in big city society, a culture that has perverted real and healthy human relations.

Photo: Enrico Nawrath / Bayreuther Festspiele

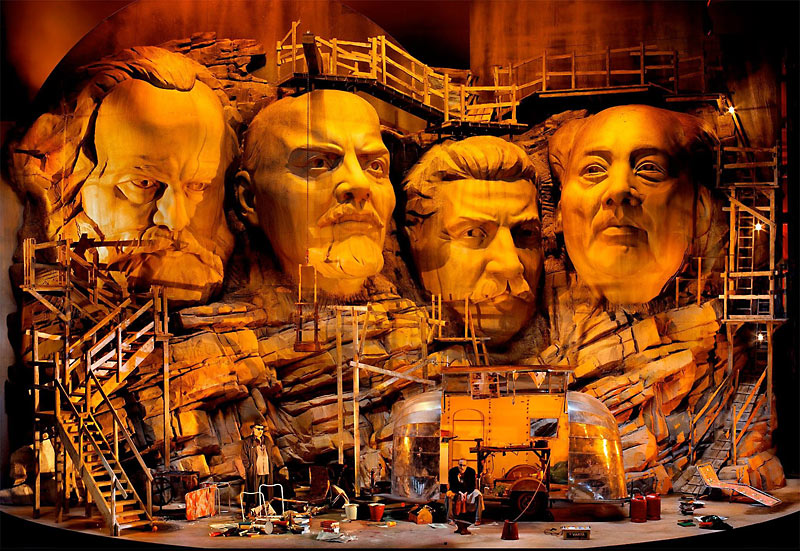

In Siegfried the dreams of freedom promised by capitalism and communism are masterfully brought together in a monumental backdrop: a Mount Rushmore carved with the heads of Communist leaders (Marx, Lenin, Stalin and Mao) in place of the US presidents. The rear of the mountain features Alexanderplatz in Berlin. In a dramatically convincing performance by Lance Ryan, Siegfried, “The Saviour”, is portrayed as unusually unsympathetic and world-weary, entirely lacking in the ability to empathize. Not only does he own a slave, but even abuses Mime's lifeless body by emptying a garbage can over him.

The ever transforming set designs of Aleksandar Denic and the spectacular lighting by Rainer Casper is really jaw-dropping. It deserves every prize there is. Scenes change from 2D to 3D, from one colour to another, cameras reveal the inside of the structures, the revolving stage makes the designs appear from different angles.

Photo: Enrico Nawrath / Bayreuther Festspiele

Müss'ges Wissen wahren manche: ich weiss mir grade genug; (Der Wanderer schreitet vollends bis an den Herd vor) mir genügt mein Witz, ich will nicht mehr: dir Weisem weis' ich den Weg!

Wolfgang Koch (Der Wanderer) and Burkhard Ulrich (Mime).

Photo: Enrico Nawrath / Bayreuther Festspiele

The theme of a life view characterized by indifference and underdeveloped emotions continues in Götterdämmerung, but this time mainly outside and inside - thanks to the video - a kebab takeaway in the GDR, where Hagen rules over a band of petty criminals. Part of the drama takes place in front of the New York Stock Exchange on Wall Street. I was expecting (or, perhaps, hoping for) a spectacular ending seeing the Wall Street building go up in flames. But, alas, in this production you are certainly not going to get what your heart desires. The final tableau, featuring Hagen and the Rhine Daughters staring out at the audience, ranks as one of the most impotent anti-operatic endings ever and rivals Peter Konwitschny’s arrogant ending in Stuttgart’s Götterdämmerung where the stage instructions were simply shown on a screen.

The Norns (Claudia Mahnke, Christiane Kohl and Okka von der Damerau) get their share of blood or paint (?) smearing. By the way, they enter the scene wrapped in garbage. The activity on stage is absurd (both in a positive and negative meaning), the characters’ reactions are generally infantile and broadly degenerate. There is little or no trace of the humanism present in Kupfer’s and Chéreau’s Ring productions.

Photo: Jörg Schulze / Bayreuther Festspiele

This Ring production takes full advantage of the revolving stage. The set by Aleksandar Denic constantly changes and creates an unusually exciting, richly detailed visual universe. We are led from an American motel on Route 66 (Das Rheingold) to the early days of oil production in Azerbaijan (Die Walküre), then onto a Mount Rushmore, to Alexanderplatz in Berlin, and then to a run-down GDR apartment block, and the Stock Exchange on Wall Street. The scenography is so fascinating that it almost threatens to make off with the whole Ring project, as did the designer Rosalie in Alfred Kirchner’s Ring (1994-1998).

At the end, as the curtain rises after the final act of Götterdämmerung, Alberich’s son Hagen, a punkish symbol of non-conformism, stands and stares at the audience. The Rhine Daughters have duly cast away the ring, forsaking power, wealth and the consumer culture the ring represents.

The hall of the Gibichungs by the Rhine.

Photo: Enrico Nawrath / Bayreuther Festspiele

The copulating crocodiles during Siegfried and Brünnhilde's love duet in Act III of Siegfried was a particular provocation to the Green Hill audience this summer, and beyond the pale for many. (Alas, if only the most stultifying, traditional stagings could also provoke such outrage.) I have no idea what the crocodile(s) are supposed to signify. There is a crocodile in the Neptune monument on Alexanderplatz. Will associations with the crocodile from Dostoyevsky’s intriguing short story, The Crocodile lead us anywhere? Or do the crocodiles in Siegfried refer to the quote “Capitalism is a crocodile you feed hoping to be the last one to be eaten”? I don’t have the answer, and I'm not sure there is even supposed to be one. Castorf spices up the four dramas with countless riddles that actively invite association. In its opening season, however, an overwhelming number of critics and audience members found this theatrical enterprise to be nothing more than irritating.

Catherine Foster's voice and stage presence is somewhat anonymous, but she generally sings well and her articulation is exemplary.

Lance Ryan delivered a dramatically convincing Siegfried, but was not up to the same standard vocally. The Bayreuth audiences showed no mercy.

Wolfgang Koch sings Wotan/Wanderer with great authority, but is given too little room for acting by the director.

Martin Winkler sings a rather "light" Alberich without the darker undertones of existential Schmerz of some of his Alberich colleagues. Winkler's acting is first-rate.

Caricatured and blunted emotions are dominant in this Ring. The systems have failed. Behind all this stands man, left in an emotional vacuum – lonely, unhappy, beset by angst, lacking the capacity to empathise. I feel that two scenes have particular resonance: in one, Siegfried sits on the asphalt, leaning against a lamppost while he sings “Doch ich bin so allein, hab’ nicht Brüder noch Schwestern: meine Mutter schwand, mein Vater fiel ...” (Siegfried,Act II). It is a potent image of loneliness in big city society, a culture that has perverted real and healthy human relations. The other key scene is when Brünnhilde sings “O Siegfried! Siegfried! Sieh’ meine Angst!” (Siegfried, Act III). Siegfried then departs; he is emotionally crippled and unable to relate to the anxiety and suffering of others. Such moments of existential significance should be worked on in the coming years, in my opinion. There is a need to break through the prevalent mood of indifference and irony.

The myriad of flickering impressions threaten to drag the entire enterprise down. In all four music dramas (and especially in Rheingold) the audience has to fight against Castorf’s many ideas to hear the orchestra. In this, its first outing, the performances required a conductor of greater Wagnerian authority and less reserve than Kirill Petrenko, who hadn’t quite come to terms with the acoustic of the Festspielhaus in his Bayreuth debut. Only in Götterdämmerung did he show his true greatness. The orchestra, however, played gloriously for him throughout. The sound was always bright and transparent, but it did lack that little extra something. Frank Castorf’s ‘Wagner’ universe is so disorienting, and so attention-seeking, that it requires a conductor who will dare to step into the ring without helmet and without gloves, a conductor who can manage to highlight what overshadows everything else: Wagner’s music.

Translation: Jonathan Scott-Kiddie

Interviews, reviews and articles

- Man geht aus dieser maßstabsetzenden Produktion selbst nach fast zwanzig Stunden Dauer nur ungern heraus, und ist im Geiste noch tagelang sowohl mit den Bildern wie mit der bereits öfter gerühmten musikalischen Gestaltung durch Kirill Petrenko beschäftigt. (Stuttgarter Zeitung, 2014)

- Mark Berry on Frank Castorf's Ring production: Das Rheingold - Die Walküre - Siegfried - Götterdämmerung

- Martin Kettle: "Castorf seems like a living embodiment of the Ring's villain, Alberich, who steals the gold, renounces love and wants to rule the world." (The Guardian)

- The Guardian Review: Das Rheingold and Die Wälkure

- The Guardian Review: Siegfried and Götterdämmerung

- "Like many theatre directors who attempt to save opera from itself, Franz Castorf ends up repeating clichés" (Financial Times)

- "If opera direction has run so dry that there is nothing left to do but ignore, fragment and provoke, the point of having a Bayreuth Festival at all must surely be called into question. [...] The new Bayreuth Ring is not just a scandal, and not only a musical triumph. It is a crisis of content for the Wagner Festival, and calls into question the future of the genre." (Financial Times)

- Juvenile pranks aside, its surreal grandeur stays in the mind. The real problem is that it attempts an excessively contorted maneuver: a double deconstruction, both of traditional, swords-and-dragons Wagner and of latter-day political interventions in that tradition. (Alex Ross / The New Yorker)

- 'Ring' director Castorf (1): 'Artistic terrorism' in Bayreuth (Deutsche Welle)

- Director Castorf (2): Art is about exceptional states (Deutsche Welle)

- Castorf inszeniert Bayreuther „Ring“ als Reise zum Erdöl ... Musik: Castorf inszeniert Bayreuther „Ring“ als Reise zum Erdöl

- Was Castorf für seinen "Ring" in Bayreuth plant

- Der Spiegel: "Götterdämmerung" in Bayreuth: Von Walhalla zur Wall Street

- Castorf, ganz Kind der Postmoderne, macht aus diesem Gestus: Schluss mit dem Kunstgeheule! Schluss mit der Interpretation der Interpretation der Interpretation! (Christine Lemke-Matwey / Die Zeit)

- Castorf takes an essentially non-Wagnerian view of the work. The result is a provocative, irritating yet fascinating production that could best be described as an 'imploded' work of art.

Wagneropera.net (2013)

The Bayreuth Festival 2017 Reviews

Mark Berry: Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (Kosky/Jordan)

Sam Goodyear: Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (Kosky/Jordan)

Mark Berry: Parsifal (Laufenberg/Haenchen)

Mark Berry: Das Rheingold (Castorf/Janowski)

Mark Berry: Die Walküre (Castorf/Janowski)

Mark Berry: Siegfried (Castorf/Janowski)

Mark Berry: Götterdämmerung (Castorf/Janowski)

Wagner Articles and Reviews on Wagneropera.net

Reviews by Mark Berry on Wagneropera.net

Bayreuth Festival

- Bayreuth 2022: Das Rheingold (Valentin Schwarz / Cornelius Meister)

- Bayreuth 2022: Die Walküre (Valentin Schwarz / Cornelius Meister)

- Bayreuth 2022: Siegfried (Valentin Schwarz / Cornelius Meister)

- Bayreuth 2022: Götterdämmerung (Valentin Schwarz / Cornelius Meister)

- Bayreuth 2019: Tannhäuser (Tobias Kratzer / Christian Thielemann)

- Bayreuth 2019: Lohengrin (Yuval Sharon / Christian Thielemann)

- Bayreuth 2019: Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (Kosky/Jordan)

- Bayreuth 2019: Tristan und Isolde (Katharina Wagner/Christian Thielemann)

- Bayreuth 2017: Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (Kosky/Jordan)

- Bayreuth 2017: Parsifal (Uwe Eric Laufenberg / Hartmut Haenchen)

- Bayreuth 2017: Das Rheingold (Frank Castorf / Marek Janowski)

- Bayreuth 2017: Die Walküre (Frank Castorf / Marek Janowski)

- Bayreuth 2017: Siegfried (Castorf/Janowski)

- Bayreuth 2017: Götterdämmerung (Castorf/Janowski)

- Bayreuth 2016: Parsifal (Uwe Eric Laufenberg / Hartmut Haenchen)

- Bayreuth 2016: Tristan und Isolde (Katharina Wagner / Christian Thielemann)

- Bayreuth 2016: Götterdämmerung (Frank Castorf / Marek Janowski)

- Bayreuth-2016: Siegfried (Frank Castorf / Marek Janowski)

- Bayreuth 2016: Die Walküre (Frank Castorf / Marek Janowski)

- Bayreuth 2016: Das Rheingold (Frank Castorf / Marek Janowski)

- Bayreuth 2014: Frank Castorf Ring: Das Rheingold

- Bayreuth 2014: Frank Castorf Ring: Die Walküre

- Bayreuth 2014: Frank Castorf Ring: Siegfried

- Bayreuth 2014: Frank Castorf Ring: Götterdämmerung

- Bayreuth 2014: Lohengrin

- Bayreuth 2012: Stefan Herheim's Parsifal

- Bayreuth 2012: Gloger's Dutchman

- Bayreuth 2012: Neuenfels Lohengrin

- Bayreuth 2011: Tannhäuser (Baumgarten)

- Bayreuth 2011: Stefan Herheim Parsifal

- Bayreuth 2011: Marthaler Tristan und Isolde

- Bayreuth 2011: Neuenfels Lohengrin

- Bayreuth 2011: The Ring for Children

More Reviews

- Berlin 2010 Cassiers Ring

- ROH 2009: Loy's Tristan

- ROH 2010: Tim Albery's Tannhäuser

- ROH 2011 Tim Albery's Dutchman

- Daniel Barenboim: Complete Wagner Operas (34 CD)

Reviews from the Bayreuth Festival

More Reviews

- Stefan Herheim: Lohengrin. Staatsoper Berlin, 2009: Den norske opera-regissøren Stefan Herheim fortryller Berlin. (Norwegian)

- Wagner i Alpene og opera i Norge (Operafestspillene i Erl - Tiroler Festspiele Erl) (Norwegian)

- Den ustanselige aktualitet: Richard Wagner i Bayreuth 1998 (Norwegian)

- Richard Wagner-Festspiele, Bayreuth 1999 Men kvinnene døde stående (Norwegian)

- Richard Wagner-Festspiele, Bayreuth, 1999. Lohengrin: Tynget av symboler, men dyster og sterk (Norwegian)

- Jürgen Flimms Ring i Bayreuth, 2000: Politikkens omslag i musikk (Norwegian)

- Schlingensiefs Parsifal: Døde harer og herlig musikk i Bayreuth (Richard Wagner-Festspiele 2004) (Norwegian)

- Der Ring des Nibelungen: Ringen er sluttet i København (Norwegian)

- Stefan Herheim: Parsifal (2008). Mystikk og begjær i Bayreuth (Norwegian)

Selected Reviews and articles

- Nila Parly: The Copenhagen Ring (Kasper Holten)

- Nila Parly: Visions of the Ring

- Bayreuth 2015: Sam Goodyear on Tristan

- Berlin 2015 Sam Goodyear on Meistersinger (Moses)

- Parsifal, Gran Teatre Liceu

- Haenchen / Kusej Dutchman

- Metropolitan 2010: Das Rheingold

- Metropolitan 2011: Die Walküre

- Washington National Opera: Götterdämmerung 7 November 2009

- Washington National Opera: Götterdämmerung 15 November 2009

- Washington National Opera: Siegfried, 2 May 2009

- Washington National Opera: Siegfried, 9 May 2009

- Berlin 2009: Stefan Herheim's Lohengrin

- Oslo: Stefan Herheim's Tannhäuser

- Los Angeles 2009: Das Rheingold

- Lincoln Center 2012: Rienzi

- Bayreuth 2010: Neuenfels Lohengrin

- Bayreuth 2013. Frank Castorf's Ring There Will Be Blood: Frank Castorf Has Entered the Ring

- Bayreuth 2010: Tankred Dorst's Ring

- Bayreuth 2010: Katharina Wagner's Meistersinger

Der Ring des Nibelungen: Articles and Reviews

Nila Parly on Regietheater: Visions of the Ring

The Cry of the Valkyrie: Feminism and Corporality in the Copenhagen Ring

Sam Goodyear, Bayreuth 2022: Der Ring des Nibelungen (Valentin Schwarz)

Mark Berry, Bayreuth 2022: Das Rheingold (Valentin Schwarz)

Mark Berry, Bayreuth 2022: Die Walküre (Valentin Schwarz)

Mark Berry, Bayreuth 2022: Siegfried (Valentin Schwarz)

Mark Berry, Bayreuth 2022: Götterdämmerung (Valentin Schwarz)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2017: Das Rheingold (Frank Castorf / Marek Janowski)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2017: Die Walküre (Frank Castorf / Marek Janowski)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2016: Das Rheingold (Frank Castorf)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2016: Die Walküre (Frank Castorf)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2016: Siegfried (Frank Castorf)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2016: Götterdämmerung (Frank Castorf)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2014: Das Rheingold (Frank Castorf)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2014: Die Walküre (Frank Castorf)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2014: Siegfried (Frank Castorf)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2014: Götterdämmerung (Frank Castorf)

Per-Erik Skramstad: Bayreuth 2013: There Will Be Blood: Frank Castorf Has Entered the Ring

Per-Erik Skramstad: Bayreuth 2010: Curtain Down on Tankred Dorst's Ring

Mark Berry: 2010 Cassiers Ring

Sam Goodyear: Laufenberg’s Wiesbaden Ring 2017

Jerry Floyd: Rheingold, Metropolitan 2010

Jerry Floyd: Die Walküre, Metropolitan 2010

Jerry Floyd Washington National Opera: Siegfried

Jerry Floyd Washington National Opera: Siegfried II

Jerry Floyd Washington National Opera: Götterdammerung Concert (2009)

Jerry Floyd Washington National Opera: Götterdammerung Concert (2009)

Mark Berry: Richard Wagner für Kinder – Der Ring des Nibelungen (2011)