Interview with Peter Konwitschny

Peter Konwitschny: I do not consider myself a representative of the Regietheater

Photos: Thanks to Bayrerische Staatsoper (Wilfried Hoesl) and Staatstheater Stuttgart. Production photos from Götterdämmerung, Parsifal, Lohengrin and Tristan und Isolde.

Peter Konwitschny (b. 1945) is one of the leading opera directors of our time. His productions are often provocative; the endings often surprising. His Wagner productions include Lohengrin, Parsifal, Meistersinger, Götterdämmerung, Holländer and Tristan. In 2008 Konwitschny was appointed Principal Director of Productions at Leipzig Opera.

Peter Konwitschny, you come from a highly gifted family of musicians. In what way has this background influenced your career as a director?

Yes, my father was Principal Conductor of the Gewandhausorchester. But one should also remember that my mother was a singer. So I grew up with music, and I believe that from this upbringing I have learned to understand the nature of music from childhood. To understand that music not only consists of tones, but rather reflects on the human existence. This, I believe to be a central prerequisite for the work of an opera director.

You have for many years been one of the leading proponents of the so-called Regietheater school. Are you ever afraid that this approach to opera is considered too intellectual for the average operagoer and thus leaves them confused?

I do not consider myself a representative of the Regietheater. Often, these directors present one single idea, such as for example staging Rigoletto in an empty swimming pool or in a slaughterhouse. These ideas are not consequentially followed through and explored, and in most cases, the singers stand next to each other on stage just as unconnected as in conventional productions.

My stagings, on the other hand, aim to return to the roots: to get to the core of the pieces, through the jungle of interpretative traditions, which in most cases, have distorted the pieces. The accusation that this is "too intellectual for the average viewer" is absurd and exposes the enemies of such theatre as opposing new insights.

In your Lohengrin production so much is happening on stage that many feel that the music is forced into the background. How do you react to this critisism?

The accusation “when too much is happening on stage, the music is forced into the background” comes from the same direction, by the same people.

In one of his productions, Wieland Wagner deleted the short Gutrune solo in Act 3 of Götterdämmerung. What is your view on making changes to the score? What would you think of the scenario where the director deleted a part of the work, or even a whole scene?

In earlier times (up until about Mozart's time) it was usual to delete and move passages. Matters obviously become more difficult when we are dealing with through-composed operas. But even Wagner and R. Strauss made proposals for cuts in their scores.

However, another aspect is important regarding alterations in the score: The theatre is not a museum. The essence of a theatrical performance cannot consist of just showing the presumed intents of the author as they were displayed at the original premiere or, rather could have been displayed at the original premiere. The purpose of a theatrical performance primarily consists in having a dialogue with the audience about essential themes in society as well as in the lives of the individual. For this, the plays provide the material, as Brecht said among other things. This also rings true for me. In the spoken theatre, incidentally, cuts, changes, edits, insertions of extraneous material is a completely normal thing. On the other hand, an interruption of a Mozart aria is like a national disaster for the opera audience. Ask yourself, why exactly is this?

Peter Konwitschny. Photo: Erik Berg / Den Norske Opera

Cosima Wagner's Diaries, 13 February 1875:

"In the morning R. talks about the possibility that the German Empire might one day rule over the entire West: ’Although world history teaches us that good never prevails, one never ceases to hope.’"

How do you interpret this passage?

Cosima's transcripts are indicative of the strange relationship between husband and wife, and I would never put my hand into the fire by stating that from what Cosima wrote Wagner said, or meant this or that.

If Wagner actually hoped for the German Empire to rule the entire West – that is of course reminiscent of the precarious and often abused phrase of the German poet Emanuel Geibel “am deutschen Wesen soll die Welt genesen” – then one may be comforted that his wish did not become reality. And I am convinced that the world is unlikely to recover once again from any empire.

Is Wagner's anti-semitism in your opinion reflected in his music dramas?

No.

Harry Kupfer once said that the Germans should stop apologizing for Meistersinger. In your Meistersinger production Hans Sachs's closing address to the people is interrupted, and the singers start to discuss nationalism. What is your view of the nationalistic elements in Meistersinger?

There are no National Socialist elements in Meistersinger. Such an opinion betrays itself as being both historically and dialectically uninformed. When Sachs speaks of "welschem Tand" [foreign vanities], it is not unfounded, as even back then, there was the danger of the overpresence of certain foreign cultural elements. For example, some German princes only spoke French and imported all sorts of oddities. Just like we today are overflooded by all things American: "You will be served at the next counter", Coca-Cola, McDonald's, etc. We know, however, that if our language dissolves or decomposes, our identity dissolves.

That is the main theme of Meistersinger, and Wagner was completely right. Such an unhistorical approach may also ignore that 150 years have passed since Wagner's texts were written, during which Wagner's terms have been filled with new content through historical events (nationalism, antisemitism, etc.). It is as if Wagner with "welschem Tand" meant: "Jeder Stoß ein Franzos, jeder Tritt ein Brit, jeder Schuß ein Russ!". The interruption of Hans Sachs's speech is intended to clarify this misunderstanding.

In several Wagner scenes a character is humiliated. Beckmesser, of course, at the Festwiese; Alberich in the first scene of Rheingold; Mime in several scenes. What is your view on such scenes where a suffering person is ridiculed?

Richard Wagner does not make his characters ridiculous. A good author does not do this. Such a black and white character portrait vastly reduces the dimensions of a character as well as an entire piece, and only narrow-minded directors make use of this.

What does the Bayreuth Festival mean for you personally? You have said that you haven't been there since you were 16 years old?

I have staged all the major Wagner operas in Munich, Dresden, Hamburg and Moscow, just as I had hoped for. The audiences as well as the important people of the European opera scene have taken notice of it. So it is no loss for me not to work in Bayreuth. Rather the opposite.

What plans do you and the Leipzig Opera have for the 200th anniversary of Wagner's birth in 2013?

That I cannot reveal yet.

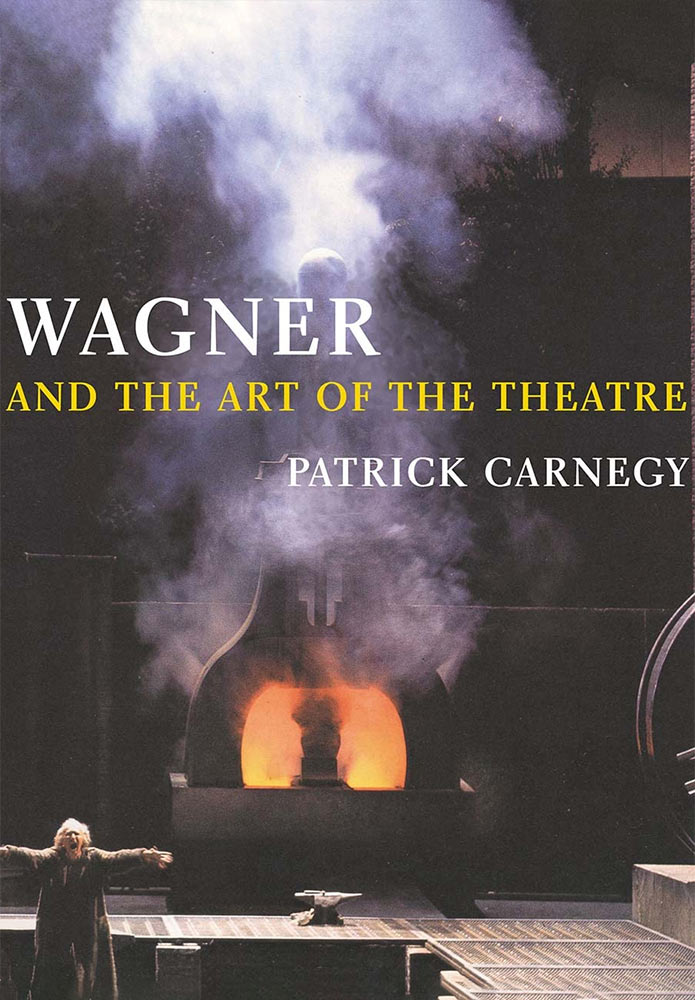

The ending of Götterdämmerung in Peter Konwitschny's Stuttgart production.

Links

- Oper Leipzig

- Article about Peter Konwitschny on German Wikipedia

- Mostly Opera

- Bavarian State Opera (Bayerische Staatsoper): Homepage + info on Mostly Opera

Literature

- Frank Kämpfer: Musiktheater heute. Peter Konwitschny, Regisseur.

- Manuel Brug: Opernregisseure heute, p. 81-98

Interviews

Peter Konwitschny: I do not consider myself a representative of the Regietheater

Alexander Meier-Dörzenbach: There is so much more than mere sentimentality to this great opera

Detlef Roth: Amfortas' Suffering is Germany's

Kasper Holten: Tannhäuser's Rome narrative is perhaps all fiction—but it is his best story ever

Lisbeth Balslev: You come to Bayreuth for the sake of art

Iréne Theorin: Isolde is incredibly intense, and that really suits me

Graham Clark: I just switched hobbies

Anne Evans: At the time I hadn’t realised what a powerful impact it made

Johanna Meier on Isolde, Bayreuth and Ponnelle

Lioba Braun on Brangäne, Bayreuth and Wagner

Stephen Gould: Tristan is the end of the line

Penelope Turing: "Heil dir, Sonne!" Meant Something in those Conditions

Daniel Slater: The creation of the self through love and death

Sharon Polyak on West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, Wagner in Israel, Bayreuth

Wagneropera.net recommends