Interview with character tenor Graham Clark (1941-2023)

Graham Clark: I Simply Switched Hobbies

The great character tenor Graham Clark talks about his career, his Bayreuth years, his work with Harry Kupfer and Ring characters Loge and Mime. Graham Clark has done over 350 Wagner performances including over 250 performances of Der Ring des Nibelungen. He has been 16 seasons in Bayreuth and done over 100 performances there as Loge, Mime, David, Steuermann, Melot and Seemann.

Graham Clark, in this interview I would like to ask you about your career as a Wagner singer and your success in Bayreuth. But let's start with you telling how your first encounter with Wagner's music dramas was.

I first sang Wagner’s music with Scottish Opera. I was a member of the company from 1975 to 1977 when we did a new production of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Initially, I sang Balthasar Zorn in 1977 and understudied David, which I sang a year later in 1978. It was a wonderfully colourful and traditional production by David Pountney and was hugely successful. I loved the experience, especially as I had no knowledge of Wagner before this. (I became an opera singer after careers as a sports teacher and as a technical officer for the Sports Council). A whole new world was revealed to me.

Graham Clark's Wagner roles:

Mime Das Rheingold

Loge Das Rheingold

Mime Siegfried

Steuermann Der fliegende Holländer

Balthasar Zorn Meistersinger

David Meistersinger

Melot Tristan und Isolde

Seemann Tristan und Isolde

Hirt Tristan und Isolde

How did your Bayreuth career start?

I was invited to audition for the role of David in a new production of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg in 1981. It was somewhat daunting and passed almost like a dream. I knew little about Bayreuth or Wagner at that time and the audition was on a Sunday morning. As I walked up to the Festspielhaus in a daze, I was rudely awakened by a very large number of American tanks, which roared past me into the station marshalling yard. I walked up the hill to the theatre in bright sunshine and was very kindly received and taken to the dark side of the stage where another five singers stood. Our names were called out in seemingly random order and I was last. I had to listen to all the others singing David’s monologue and increasingly I really wondered why I was there as they were all so wonderful. Finally my name was called and I thought nothing ventured, nothing gained, let’s go for it. We were then taken back to a room where Wolfgang Wagner appeared beaming, thanked us for coming and said another singer had still to be heard. It was some time later before I was told that I had been chosen. Extraordinary. I was thrilled.

You have done over 100 performances in Bayreuth over 16 seasons. I guess one could say that these summers must have been special for you since you chose to return year after year?

The atmosphere at the Festspielhaus has always been very special. We were grilled hard and often on both music and text and the rehearsals were intense, and that has its own fierce attraction. The audience reaction to performances in Bayreuth is extreme with wild and prolonged applause and cheering and also vociferous booing. Our Meistersinger performances between 1981 and 1987 averaged something like forty-five curtain calls over the seven years I sang David. That is over an hour of curtain calls some evenings. Quite extraordinary.

Wolfgang Wagner always sat next to me during the final scene of the final performance of Die Meistersinger, dressed in a smock and costume and drank my beer! Most importantly, in my early years there all the singers remained at the Festspielhaus throughout the season and we had a really fantastic social life both inside and outside rehearsals and performances. For example, we had many parties and receptions, tennis tournaments and even a Solisten football team that played a team of German internationals including Beckenbauer and was recorded on TV.

The hub of the Festspielhaus at Bayreuth is the Kantine. Everyone meets there – singers, chorus, technical crew and orchestra. The excitement of rehearsals and performances is palpable in the Kantine too. You must remember that all the season’s operas are performed at the same time at Bayreuth, unlike, for example, Salzburg where the operas are spread out over a long period. Consequently, we see and meet all our colleagues who are in all the other operas on a daily basis, talk about our experiences and watch all the main rehearsals. It is a vibrant atmosphere. Clearly, the standard of performances is exceptional too – controversial sometimes, yes, but always enthralling. The orchestra and chorus are par excellence year in year out and a wonder to hear and watch. The acoustics, the stagings and the demands of such high profile performances are a magnet for anyone interested in theatre. I loved my time there, I really did, and have so many wonderful memories. It certainly wasn’t easy at times and I was stretched to the limit, but it was hugely rewarding.

Heinz Zednik writes in his autobiography about the pros and cons of the extensive rehearsals in Bayreuth. What are your thoughts on this?

I love rehearsals. It is a time of experimentation, exploration and carefully studied examination of music and text. With astute coaching so much can be achieved. New vistas are opened up, new perspectives are explored and your understanding of the music and text takes on new dimensions and gathers pace and balance.Your personal technique and understanding are tested and adjusted and your awareness of the psychological dimensions of the characters develops profoundly. Every day of rehearsals can bring immense rewards.

When we did the 1988-1992 Ring with Barenboim and Kupfer, we started full rehearsals for the entire Ring in April 1988, but rehearsals for Siegfried began in 1987, one year before the Ring year and between performances of Die Meistersinger. We had the full set and props for the 1988 Ring, one year in advance! Siegfried Jerusalem and I rehearsed extensively the first two acts of Siegfried. I had already sung both my roles, Loge and Mime, elsewhere before Bayreuth, but our prolonged rehearsal period was absolutely revelatory. We were frequently exhausted after a long day’s rehearsals, but exhilarated too. We were convinced it would be an extraordinary production and series of performances and our exhilaration and thirst for success was intoxicating. Of course, the prime reason for these feelings was having the wonderful luxury of working with Barenboim and Kupfer in tandem. They were an extraordinary team and gave us so much undivided attention, care and love. It was a quite unforgettable period and undoubtedly one of the major highlights of my career.

Your Loge (Das Rheingold) and Mime (Siegfried) in the Harry Kupfer production 1988-1992 was a huge success among both critics and the festival audience. Please tell us about how you experienced these Bayreuth years.

The years passed all too quickly, although each year was extremely demanding. Rehearsals were equally intense each year as in the first year. There was never any sense of simple repetition. Each year the operas were studied deeply and carefully and adjustments made. The performances grew and matured, but that maturity came through diligent application and careful further exploration. We never cruised! As a result, our exhilaration, mentioned above, never, ever sagged.

You seem to me the ideal singer for a Kupfer production, being so physical and able to act – not to mention your comic talents that suits the Kupfer style. Has your cooperation with Harry Kupfer been especially important for you?

Yes, Harry and I became good friends throughout those years and subsequently. He had very clear ideas about the production he wanted and we searched and struggled to create it for him. We had many laughs in rehearsals as I tried and sometimes made a complete dog’s dinner of some of the production he demanded. But perseverance and trial and error over the long period of rehearsals ironed out the problems. Nothing demanding works first time, especially in opera. It takes endless attempts to approach the ideal required, and patience and trust. I had that in Harry and I hope he had it in me. His voice still rings in my ears.

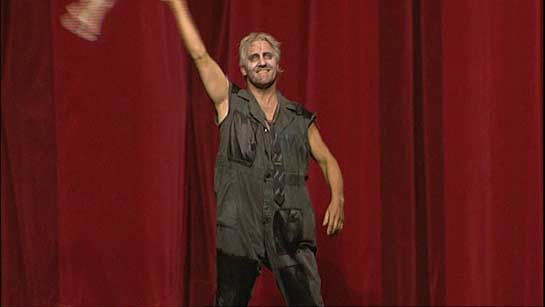

Graham Clark (Mime) and John Treleaven (Siegfried) in Harry Kupfer's production of Siegfried at Gran Teatro del Liceu in Barcelona. Available on DVD from Opus Arte.

The cooperation between Daniel Barenboim, Harry Kupfer and the singers were quite extraordinary, and something I guess repertory theatre singers never experience?

Both Daniel Barenboim and Harry Kupfer devoted the whole of Spring and Summer of 1988 and much of Summer 1987 to make the Ring such a success. They were always there at rehearsals, seven days a week in 1988, 10am to 6/7pm, from mid April to the end of performances at the end of August. Discussions about music, production, props, costumes, technical problems were always a three way process between Harry, Daniel and the singer. Deep and sincere cooperation was undoubtedly the key to the success. We had extensive musical rehearsals, both solo calls and ensemble calls with Daniel. Sometimes Harry would attend to clarify a point whilst Daniel was always at production calls to ensure the highest musical standards. We owe them so much and I learnt so much. Our team of musical coaches was rather extraordinary too – Tony Pappano, John Fiore, Simone Young, Ascher Fisch, Tony Legge, Lionel Friend, Susan Webb, amongst others.

What is the difference of singing in Bayreuth compared to the other opera houses?

The acoustics are so extraordinary. The famous hooded and deep orchestral pit gives it a unique sound. It is hard to describe and more technical experts than myself will give you a better appraisal, but it is clear, resonant, warm, in some instances quite ethereal as in Parsifal and sometimes quite shatteringly loud on stage. But that is only part of the equation. There are other aspects of singing in Bayreuth that are unique to the house. First of all the performances begin at 4pm for those with intervals and the intervals are one hour long. The public mood changes according to the opera performed – on Tristan days there is love and magic in the air, on Hollander days there is a certain swing in conversation, on Ring days there is heavy study, opinion and argument in the air, Parsifal quietens and soothes the soul whilst Meistersinger days create joviality and fun. As performers we sense these moods and they do affect our performances accordingly. Other factors are that the entire crew and orchestra are there because they want to be there for the summer festival and to be involved in the Wagner experience. Some have worked at the festival for over 30 years, summer in, summer out.

The chorus is second to none, again with many loyal, long-serving members. The intense working schedule and the superb facilities are a joy and the seven-day weekly timetable means that you forget the rest of the world exists for the period you are there. But first and foremost, the most important factor is that you are personally invited by the grandson of Richard Wagner to attend and perform Wagner’s operas in his own house and theatre. Nothing beats that honour.

Do you think singers and conductors still feel that it is an honour to perform in Bayreuth?

Absolutely. There is no other opera house in the world with a direct living family link to the composer and creator of his own Festival.

The last time I visited Bayreuth (in 1997), the question of who were to succeed Wolfgang Wagner as Festival leader was a very hot topic. Gottfried Wagner had just released his book "Wer nicht mit dem Wolf heult", and Wolfgang Wagner was under attack for his way of running the festival. Now, more than ten years later, the succession soap opera is still not over. How did you experience this?

I didn’t. Wolfgang Wagner was very much in control, it is his family house and we were there at his personal invitation.

What are your thoughts on the Bayreuth Festival's future?

I very much look forward to the continuing Bayreuth Festival’s expression of the Wagnerian ideal, whatever that is. For me, it is an endless search to try to satisfy a deep curiosity of matchless music and text.

Now, Loge is certainly one of my favourite characters in the Ring. He is hilariously funny, intelligent, manipulative, dangerous and ironic – a dream for a character tenor, I would guess?

Yes, Loge is great fun to play. Fire has many facets and can be represented in many ways. There are sparks and very small fires to huge conflagrations. Some fires are terrifying with enormous destructive force, whilst others are considered comforting and warm, especially in winter, yet have an inherent danger. Some are blue in colour, such as the gas fire on a kitchen cooker, and appear to be cold. But put your finger in and, of course, it is burnt. That fire has a constant shape too, whereas a bonfire dances and has many branches of fire, all equally dangerous of varying length and strength. Fire can therefore be very controlled and contained or very uncontrolled and wild. These attributes offer the role of Loge immense opportunities for characterisation and vocal colour and Wagner’s music and text reflect these characteristics. At times it is loud and declamatory whilst at others it is beautifully lyrical. It is also tight, brief, mocking, ironic and sarcastic, full of mood changes, with crisp, sharp, pointed and sarcastic alliteration. I tried to reflect these differences both physically and vocally throughout the performances and found it a fascinating challenge and a delight to explore.

Do you see Loge as a kind of a jester?

He certainly mocks Wotan and the Gods, loathes Alberich and has a mild sympathy for Mime and Fasolt. His biting irony and cutting remarks could certainly be construed as those of a court jester, but he is no fool. He is a demi God of intellect and manner and who has all the Macht, power, he needs. Fire has natural power. Loge doesn’t seek it, nor does he need it. Hence, he is able to treat the Gods with disdain and contempt. But he never resorts to simple posturing and tomfoolery. If he did, it would weaken his authority and stature.

Loge and Mime are never rewarded, no matter how hard they try. Immer is Undank Loges Lohn. He is only accepted by Wotan, and is "halb so echt" as the gods. Is Loge a tragic character?

I don’t think so. He is a loner, a fixer, a commentator, a mediator and a judge of character and situation. But he loves to tempt and to test the Gods and contrives and manipulates situations for them to bite the bait and stumble. I think he is far too fascinating, quicksilver and intellectually adroit to be considered pathetic.

Ernest Newman describes Mime as "a thing of evil, and, in his debased way, of power for evil". What is the nature of this evil?

Mime is utterly duplicitous and conniving. Early in Das Rheingold, without prompting, he declares his burning desire to hold the Ring and have power over everyone. This is the motivating force of his psyche. He will explore any way he can to win power, and will willingly kill to get it. He has lived a pretty miserable life under the yoke of his brother and underground. He desperately wants to escape the tyranny, but he is only a technician and hasn’t the intellect to design the Tarnhelm or his own destiny, only to make the Tarnhelm according to instructions from Alberich.

His whole appearance in Siegfried is a study of his torment to win the Ring and destroy Siegfried. Nothing else interests him. The unwritten story of what happened at the end of Walküre confuses the issue for him too. Did he see Sieglinde die, did he snatch the baby Siegfried or was it thrust into his hands forcing him into another miserable dilemma? If it wasn’t for his duplicity, he could be considered rather pathetic.

According to stage directions for "Young Siegfried", Wagner wanted the comic elements in the characterization of Mime on stage to be toned down. In productions of "Siegfried" today comedy dominates, don't you agree? And doesn't this make Mime harmless?

Yes, of course it can. But I like to see some comedy in Mime’s scenes because it highlights his stupidity, his crude thirst for power, his meanness and his irrepressible conniving. Additionally, the youthfulness and immaturity of Siegfried becomes more poignant and apparent. However, it shouldn’t necessarily dominate the act and detract from the energy and thrust of the mission of the young hero. In any case, in the full scale of the Ring, Mime is harmless from the beginning and somewhat ridiculous in his passion for power.

Alberich is a victim of the Rhinemaiden's mockery and rejection, Mime is a victim of Alberich's repressive tyranny and Siegfried is a product of growing up with a selfish father ruled by self-pity, anxiety and lust for power. They all lose something of themself. But instead of turning the grieving process into "mitleid" and deeper insights, they all become more or less sadistic and destructive. Do you find the vicious mockery of suffering people in Rheingold and Siegfried (not to mention Meistersinger) disturbing?

The lust for power is a desperate act and has an infectious fascination for many. It surrounds us daily and has always existed. Sadly, it will never disappear. Dictators’ lives end in ignominy. In the meantime they have made many people’s lives utterly miserable. I think it is quite appropriate to highlight the consequences of the lust for power and the ensuing suffering in any way and hopefully strive for a far better life. The arts and music give us that opportunity.

What is your view on traditionalist productions versus the so called "Regietheater"?

Both have their place and can be justified accordingly. I enjoy the challenge of both.

Can you tell us any practical jokes you have experienced on the stage? Or something that went terribly wrong?

Yes, we had many jokes between us on stage, both in Bayreuth and elsewhere. I put a fish in a prop for Siegfried Jerusalem once in Bayreuth; the final Meistersinger performances between 1981 and 1987 always had a joke at some point, usually involving Hans Sotin, once as a Putzfrau throughoutact one cleaning the windows of the church, and, on another occasion, sitting as Niklaus Vogel, the ill Meister, in the role call in act one.

The anvil broke in the opening 10 minutes of Siegfried act one and couldn’t be smashed by Siegfried at the end of the act in one performance, and so on and so on. Live performances are just that – live – and anything can go wrong. It’s almost Murphy’s Law – if it can go wrong, it will. The trick is to camouflage it somehow, which is easier said than done and usually ends up making it more obvious.

Who is the Graham Clark when he is not performing or rehearsing? What do you do that are not related to opera?

I was a sportsman for many years before I was a singer. I simply switched hobbies. They are now reversed. Our grandchildren are the focus and joy of our older age.

Some Wagner productions in which Graham Clark has sung:

Der Ring des Nibelungen (Harry Kupfer), Bayreuth

Der Ring des Nibelungen (Otto Schenk), Metropolitan

Der Ring des Nibelungen (Jürgen Flimm), Bayreuth

Der Ring des Nibelungen (Pierre Audi), Amsterdam

Der Ring des Nibelungen (Harry Kupfer), Berlin/Barcelona

Der fliegende Holländer (Harry Kupfer), Bayreuth

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (Wolfgang Wagner), Bayreuth

Pictures from Das Rheingold and Siegfried in Harry Kupfer's staging at Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona. Available on DVD from Opus Arte.

Wagneropera.net recommends

Interviews

Peter Konwitschny: I do not consider myself a representative of the Regietheater

Alexander Meier-Dörzenbach: There is so much more than mere sentimentality to this great opera

Detlef Roth: Amfortas' Suffering is Germany's

Kasper Holten: Tannhäuser's Rome narrative is perhaps all fiction—but it is his best story ever

Lisbeth Balslev: You come to Bayreuth for the sake of art

Iréne Theorin: Isolde is incredibly intense, and that really suits me

Graham Clark: I just switched hobbies

Anne Evans: At the time I hadn’t realised what a powerful impact it made

Johanna Meier on Isolde, Bayreuth and Ponnelle

Lioba Braun on Brangäne, Bayreuth and Wagner

Stephen Gould: Tristan is the end of the line

Penelope Turing: "Heil dir, Sonne!" Meant Something in those Conditions

Daniel Slater: The creation of the self through love and death

Sharon Polyak on West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, Wagner in Israel, Bayreuth

Graham Clark

Graham Clark has delighted audiences in over 350 Wagner performances – including over 250 performances as Mime and Loge in Der Ring des Nibelungen.

Clark was a Director of Physical Education in three schools, and was a Senior Regional Officer with the Sports Council before he decided to devote himself to singing. He made his operatic début with Scottish Opera in 1975. His first Wagner roles were Balthasar Zorn and and David (both in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg).

He visited Bayreuth 16 seasons and has done more than 100 performances at the Bayreuther Festspiele. He has been a regular guest at the Metropolitan Opera and operahouses in Aix-en-Provence, Amsterdam, Barcelona, Berlin (Deutsche Oper, Deutsche Staatsoper), Bilbao, Bonn, Brussels, Catania, Chicago, Dallas, Geneva, Hamburg, Los Angeles, Madrid (Real, Zarzuela), Matsumoto, Milan La Scala, Munich, Nice, Paris (Bastille, Champs Élysées, Châtelet, Palais Garnier), Rome, Salzburg, San Francisco, Stockholm, Tokyo, Toronto, Toulouse, Turin, Vancouver, Vienna, Yokohama and Zurich.

Clark has received three nominations for "Outstanding Individual Achievement in Opera" Awards (1983, 1986, 1993), including an American Emmy. He won the Sir Laurence Olivier Award in 1986 for Mephistopheles in Busoni's Doktor Faust. He was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Letters, Loughborough University, in 1999.