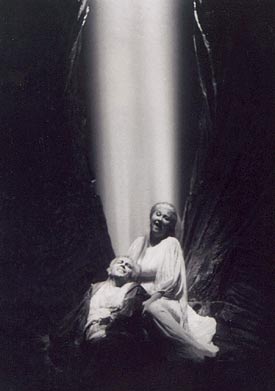

Johanna Meier: Isolde appearing in a dream

Johanna Meier, one of the foremost Wagnerian sopranos of her era, is known for the broader and younger audiences as the Isolde in Jean-Pierre Ponnelle's production in Bayreuth. It is available on DVD, and will be the preferred Tristan on DVD for many. In this interview Meier talks about her Bayreuth summers as Isolde, the work with Ponnelle and Barenboim - and the ending: She never sang Liebestod from the orchestra pit during performance, as Spotts and some German critics have claimed!

Johanna Meier, you were the first American to sing Isolde in Bayreuth. But this was, I think, your fifth Isolde?

No, sixth: Mexico City, Toronto, Welsh National Opera, Seattle, and Lyons all preceded Bayreuth.

How would you describe your three summers at the Bayreuth Festival?

My summers in Bayreuth were a delight. The first year was very stressful, putting together a detailed new production, being “on display” as the first American to sing Isolde, and getting accustomed to the demands of the press and public. The second and third year were much more relaxed; I had found a pleasant house to rent in Altenplos, in the countryside near Bayreuth, and I was able to enjoy my surroundings and get to know more of my colleagues.

The Wagner family and the Festspielhaus staff were very gracious to me. I felt that everyone was a little worried at having an American come to do this highly visible role, in case I should not fit the image which was expected. However, when it was realized that I spoke fluent German, and that I was not going to arrive chewing gum and wearing blue jeans, everyone relaxed, and I was cordially welcomed. It was very apparent to me that all of the staff, and most of the citizens of Bayreuth had a very real love and respect for the music and the performers, and this creates a very unique atmosphere for the singers. I will always count the summers spent there as highlights, and my memories very pleasant ones.

Singing at the Bayreuth Festival means hard work for little money – and a ruined holiday. What was the magnet for you?

Summertime did not automatically mean holiday time for me; in the United States I always had a number of summer engagements: the Metropolitan opera performances in the New York City parks, Festivals at Ravinia (Chicago Symphony) and Tanglewood (Boston Symphony), the Cincinnati Summer Opera, the Seattle, Washington Ring Cycle, the Spoleto Festival, etc. Singing in Bayreuth is of course every Wagnerian’s dream, and I was delighted to have the opportunity. Working with fine colleagues in an atmosphere totally devoted to Wagner’s works, in the quintessential Festspielhaus productions, was an experience which I will always treasure.

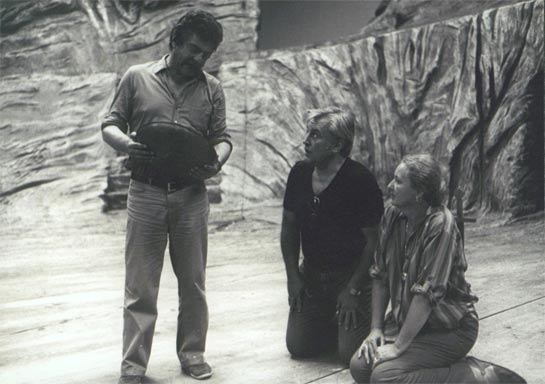

How would you describe the rehearsal work in Bayreuth?

The rehearsals were intense. I had worked for a week in Paris with Barenboim before I arrived, so musically things were pretty well organized. Ponnelle was an extremely demanding director, and very insistent on small details. He tended to look at every scene through his squared fingers, as though he were looking through the lens of a camera. My colleagues were pleasant to work with, but the intense repetition, particularly of Act I, was tedious.

There have always been a myth out there that it is easier to reach above the orchestra in Bayreuth than in other opera houses. Manfred Jung once said that it on the contrary can be more difficult. How did you experience this?

I was forewarned by my colleagues that I would not get the sense of ‘vocal return’ in the house that one experiences most places, and so the tendency is to push the voice to achieve this. I was advised to sing at my normal level, and because I knew what to expect, I felt comfortable. I had originally prepared the role with Sir Reginald Goodall, a well-known Wagner specialist and protégé of Furtwangler. He pointed out that page after page in the ‘Tristan’ score is marked Piano, and even Pianissimo, as opposed to the double decible singing which many Wagnerians espouse. Since I am a Lyric-Dramatic, this was much more suited to my voice, and Barenboim was totally in agreement with this approach. It also permitted me to give more attention to the text, and create more of a ‘color palate’ of expression through the words.

How would you describe Ponnelle's Tristan production?

Visually the production was stunning, particularly the 2nd Act, with the great tree and the lighting effects behind it. The costuming for Isolde was rather a strange mixture, as the 1st Act costume was distinctly contemporary, while the 2nd Act was more traditional.

How was it to "wear" the giant cape in the 1st Act?

The giant cape was hand-painted silk and when opened out covered almost the entire stage. I knelt in the center of the stage before the curtain went up, and it was arranged around me on the floor by several assistants; then about 20 minutes into the act I had to leap up and drag it around with me… It weighed around 65 pounds, and had to be stored on the floor of the ballet rehearsal room, as it was too large to be hung up! I also had to balance the large flower crown on my head, which I had to remove and ‘destroy’ while I was singing.

The ending of this production, with Isolde's return as a dream or a fantasy, is now a classic interpretation. But what now seems so obvious wasn't so obvious at all. The first year had another ending, didn't it? With a totally empty stage after the Liebestod?

With a month’s rehearsal, things should have been set, but we discovered only in the last week that Ponnelle really had very little planned for the 3rd Act. As I will subsequently explain, the same ending was used all three years, with minor adjustments, and somewhat hastily decided upon. Isolde was present at the end of the Liebestod.

I've read that Ponnelle at one point wanted you to sing the third act from the orchestra pit and that Wolfgang Wagner vetoed this. Can you tell us what happened from your point of view?

Ponnelle imagined Isolde would never appear, but sing from the pit, which idea was not favored by me, nor by Barenboim, nor by Wolfgang Wagner, so in the final week of rehearsal Ponnelle began experimenting with various possibilities. Isolde here, Isolde there, Isolde arrives early, Isolde arrives late, etc. Since the 3rd Act set consisted of a dead tree on top of a rocky outcrop supposedly in the midst of water, the options were very limited. The final staging was decided on Opening Night, when I was informed in my dressing room between the 2nd and 3rd Act which version we would do. This version was used in all three years of the production, although it has been erroneously reported both in reviews and books that Ponnelle’s first concept of Isolde singing from the pit was used. I have had numerous occasions to correct this misconception, which was evidently started by several German critics who reviewed the production, never having actually seen a performance.

How did you react to Ponnelle's idea that Isolde's appearance should just be a dream when this was first presented to you?

The concept of Isolde appearing in a dream was not unappealing; however I found it logistically very inappropriate on a number of levels. The first was naturally because it radically affected the development of Isolde’s characterization. Working hard for two acts to create a believable, complex character, and then to be suddenly thrust into the middle of the brass section in the pit was very disruptive; it also affected the sound and presence of the voice in the theatre, as Barenboim pointed out.

You didn't have many seconds to disappear before the lights went out to reveal that Isolde's return was just a dream. How exactly did you disappear?

I had entered up a back staircase and arrived in the middle of a dead tree, so without going back down the stairs, I would have had little opportunity to disappear. The film which was subsequently made by Unitel shows Isolde ‘disappearing’ through camera editing, I believe.

What do you think of this ending now?

My feeling at the time, which may or may not be correct, was that Ponnelle simply ran out of time, as he spent so many weeks detailing the 1st and 2nd Acts. It was a solution which may have appeared to be effective and simple, but actually created too many problems logistically to be easily workable.

Did you ever work with Jean-Pierre Ponnelle before Bayreuth?

I had never worked with Ponnelle before Bayreuth, but did work with him afterward, in a production of ‘Der fliegende Holländer’ at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

This Tristan was Daniel Barenboim's first production in Bayreuth. How did you experience working him?

I enjoyed working with Barenboim a great deal. He had a lyrical approach, which suited my voice well, and always worked closely with the singers to achieve his effects. He was very supportive and the only problem I encountered was that he would sometimes shift tempi too rapidly for the singers to adjust; I felt that this may have been due to his long experience as a solo artist, where he could make more rapid changes in mood on the piano than when he was conducting a large orchestra and a group of singers in performance.

Barenboim later conducted the Harry Kupfer Ring (1988–92). During rehearsals for this Ring he worked very close with Kupfer and the singers. Was this the case also with Ponnelle and the singers in this Tristan?

Barenboim was present at all rehearsals, and ‘built’ the performance together with Ponnelle and the singers. In many ways it was an ensemble performance, which I feel opera should always be, as opposed to a ‘star’-focused presentation.

How was it to sing opposite René Kollo?

Rene and I worked well together; I subsequently sang with him several times: in Vienna, at the Metropolitan, and also as a guest on his television special from Budapest. In addition, we shared a mutual love for our dogs; he had a Boxer named Erna, and I had my Pug, Rosie, with me in Bayreuth.

I totally fell in love with your psysical approach to the singing, the way your body is swaying and moving along with the music. Is this how you always sing, or was this something Ponnelle wanted?

That is totally my own, and has been incorporated in all of my work. I studied ballet from the time I was three years old, and later began studying various kinds of body movement while at the Manhatten School of Music in NYC. I assisted the teacher there, and eventually took over teaching the class for a year when she unexpectedly died. That is also a strong part of the Opera Institute program here in South Dakota, as I feel that a singer should perform using the entire body, and so many just sing "from the neck up". The singer's body is an integral part of the character interpretation, and must reflect the emotions which are being dramatized. The music has to flow through the body like blood, and the singer must be free from tensions and physically supple to allow this to happen. Combined with the full appreciation and utilization of the text, this offers a total performance.

How did you experience the Bayreuth audience?

The Bayreuth audiences were very warm and enthusiastic. The count of curtain calls was always an important feature of each performance, the fans waiting at the Stage Door, and of course one was recognized on the street and in the surrounding towns. It was a very gratifying experience.

In 1997 you started the School of Opera and Vocal Arts. What is that?

The Johanna Meier Opera Theatre Institute is part of a larger Black Hills Summer Institute of the Arts, run in conjunction with our State University here in Spearfish, South Dakota. Drawing on a faculty of former opera colleagues, I have put together a two-week intensive training program for young singers during June. They come to us from all over the United States and Canada (one even from Sweden) and we provide a concentrated period of instruction designed to help students transition from a school/studio situation to entrance-level for a professional career. Classes in Body Movement, Stage Presence, Diction and Interpretation, and the Business of Music are interwoven with staged performances, recitals, and Master Classes. This year we celebrated our 10th Anniversary.

Kirsten Flagstad always advices singers to be patient and wait singing the great Wagner roles. Do you have any thoughts on how a dramatic soprano should develop her voice?

I was fortunate in that both my teachers and my career allowed my voice to develop slowly. I auditioned in Germany shortly after graduating from the Manhattan School of Music in New York, and was immediately offered Wagnerian roles. Fortunately I was wise enough to realize that singing many performances of heavier roles at that stage was unwise, and I returned to the United States, ultimately beginning at the New York City Opera. There I sang a great deal of Mozart, which introduces the singer to long-line phrases, but with light orchestration. Gradually I began to mix in Strauss, which has the same long phrases, but with a heavier orchestra, and by the time I began to sing Wagner, my vocal stamina was sufficient to ‘ride’ the big orchestra. Since essentially I was a lyric-dramatic soprano, I continued to mix in other repertoire such as Norma, Trovatore, and Rosenkavalier, which kept the voice flexible and supple. Only toward the end of my career did I exchange Chrysothemis for Elektra, and Sieglinde for Brünnhilde. The final performance of my career was in 1994 as Elektra.

Johanna Meier's Wagner roles

Elsa - Lohengrin

Eva - Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

Senta - Der fliegende Holländer

Sieglinde - Die Walküre

Brünnnhilde - Die Walküre

Isolde - Tristan und Isolde

Wesendonck Lieder

Also: Siegfried Wagner Lieder

Interviews

Peter Konwitschny: I do not consider myself a representative of the Regietheater

Alexander Meier-Dörzenbach: There is so much more than mere sentimentality to this great opera

Detlef Roth: Amfortas' Suffering is Germany's

Kasper Holten: Tannhäuser's Rome narrative is perhaps all fiction—but it is his best story ever

Lisbeth Balslev: You come to Bayreuth for the sake of art

Iréne Theorin: Isolde is incredibly intense, and that really suits me

Graham Clark: I just switched hobbies

Anne Evans: At the time I hadn’t realised what a powerful impact it made

Johanna Meier on Isolde, Bayreuth and Ponnelle

Lioba Braun on Brangäne, Bayreuth and Wagner

Stephen Gould: Tristan is the end of the line

Penelope Turing: "Heil dir, Sonne!" Meant Something in those Conditions

Daniel Slater: The creation of the self through love and death

Sharon Polyak on West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, Wagner in Israel, Bayreuth

Wagneropera.net recommends