Girl Power in a Man’s World

Lise Davidsen in a league of her own. Photo: Erik Berg

Lise Davidsen as Senta in a concert performance of The Flying Dutchman at Oslo Opera House, August 22 and 24, 2024

Musical direction: Edward Gardner

Opera Choir and Opera Orchestra

Daland: Brindley Sherratt

The Dutchman: Gerald Finley

Senta: Lise Davidsen

Erik: Stanislas de Barbeyrac

The Steersman: Eirik Grøtvedt

Mary: Anna Kissjudit

Lise Davidsen (Senta), Edward Gardner and Gerald Finley (Dutchman). Photo: Erik Berg

What is The Flying Dutchman about? Storms on the Norwegian coast? True love? Is the drama misogynistic? Is Senta insane? Is it a relevant music drama for people of today?

Recently returned from Bayreuth (where I saw, among other performances, Dmitri Tcherniakov's intense Holländer), one of the first things I do is experience Lise Davidsen in a concert version of The Flying Dutchman at the Oslo Opera House. Two out of two concerts. Some people clearly can’t get enough of Wagner.

No matter how absurd it may seem to perform Wagner in concert form, that was what the Opera House offered Oslo audiences this fall: two concert performances of Wagner's first (relatively) “mature” work. Recordings were made for later release on CD.

The Flying Dutchman marks Wagner’s transition from “libretto producer to poet” (according to himself) as well as his revolutionary shift from number opera to music drama. The music drama unfolds in longer musical-dramatic scenes rather than being divided into numbers, which – on the scale Wagner executed it – was groundbreaking. This created a completely new flow, which Wagner would further develop and perfect later.

For someone passionate about how directors interpret and grapple with Wagner's music dramas in an attempt to make the works relevant for today’s audiences, concert versions feel like a wedding where the bride or groom is absent. Wagner’s music dramas are designed to convey a complete experience with singing, orchestra, set design, lighting, and acting.

Judging by the applause, there were likely not many in the audience at these two concerts who missed a full opera production as much as I did. Some conservative (in some cases reactionary) opponents of “modern productions” would rather prefer to hear the music without context and without resistance. They got exactly what they wished for.

Die Frist ist um

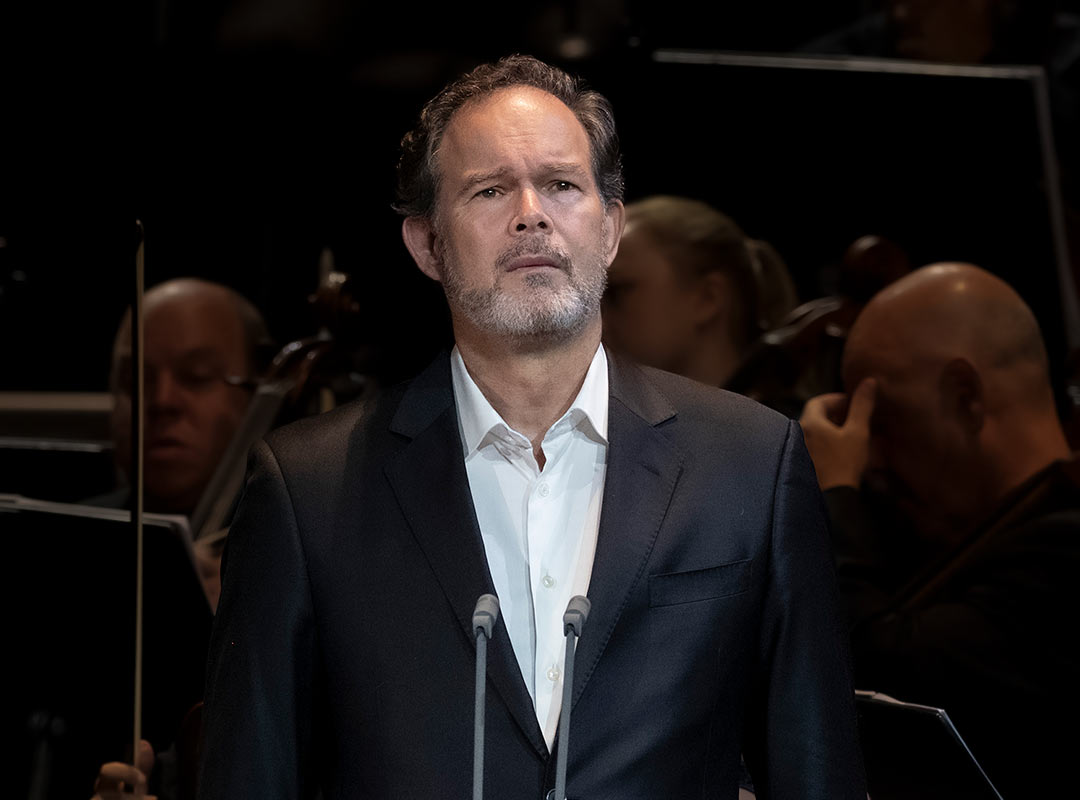

Gerald Finley as the cursed Dutchman. Photo: Erik Berg

Wagner suggests in Eine Mitteilung an meine Freunde (1851) that the Dutchman reflects “an age-old feature of man’s character … with a power that grips the heart”, “a longing for the respite from the storms of life.” Yearning for death and longing for redemption are not everyday concerns for people today, but in Wagner's world, these are core themes. The context in The Flying Dutchman is rooted in Christianity, and the Dutchman's longing for redemption can be understood as humanity's hope for salvation. The Dutchman's punishment is truly unreasonable and senseless. Just because he stubbornly refused to give up when rounding a cape, Satan condemned him to an eternal life on the seven seas. Fortunately for him, an angel of God decided that every seven years he would have the opportunity to be freed from the curse if he found a woman who could remain loyal to him until death. The concept of loyalty (Treue) is the crux here. What does it mean? That the woman should never leave him? That she should not be unfaithful and fuck other men? That she should be submissive? Or perhaps be the chosen one by God to redeem him, to save him …

At the start of the drama, it has been seven years since the Dutchman last had the chance to be freed from the curse. Now a new opportunity presents itself.

The Dutchman we experienced in these two concerts was extremely sympathetic. Bringing in Gerald Finley as the Dutchman was truly a coup. He is one of the world's leading lieder singers, and the subtle vocal artistry he masters in that genre is carried into his role as the Dutchman. Finley sings the role with a remarkable authority. He shapes words and phrases with first-class skill, conveying the Dutchman's desperation, loneliness, pain, and yearnings without descending into pathos. Every word is masterfully colored and shaped with nuances and meaning. Finley does not merely sing the Dutchman; he is the Dutchman. Although he may not have Michael Volle's power, his performance stands out with such nuanced and exemplary vocal use and expression that one never misses the power. A highlight!

To the extent that Finley was not audible over the orchestra and Lise Davidsen, it is Gardner's and Davidsen's fault. They sometimes pursued their own (volume-wise high) path without showing consideration or adjusting the strength.

On the CD, this will likely be mixed and sound much better than at the concert.

Finley's interpretation made it clear that his Dutchman is not seeking love (Liebe). There is something much larger at stake. “The dark glow I feel burning here,/should I, unfortunate one, call it love?” he asks himself and answers that no, it is the longing for redemption. Many have turned the drama into a love story between a tormented man and a hopelessly infatuated and eccentric nutcase of a girl with a savior complex, but Finley and Davidsen puncture such a meaningless interpretation, which robs Senta of her power and autonomy, and makes it difficult to take the opera seriously.

Lise Davidsen Show

Lise Davidsen as Senta in The Flying Dutchman, concert performance, The Norwegian National Opera. Photo: Erik Berg

Lise Davidsen’s strong and determined Senta is a perfect match for Finley's tragic Dutchman. She, too, is not seeking love (Liebe); it is intense compassion (Mitleid/Mitgefühl) for the tormented man that drives her. She does not have a celebrity crush on the weather-beaten Dutchman—she has a divine calling. In the universe of the drama, she actually possesses a divine power; she does manage to redeem the Dutchman through her sacrificial death.

The concert was marketed as a Lise Davidsen show. It is understandable that it was primarily her that the audience came to experience. She did not disappoint.

Thursday was the first time she sang the role of Senta, and Saturday was (probably) the last. She performed the role only for this concert and the recording for Decca, so opera director Randi Stene was right when she said before the performance that this was a historic event. Greater challenges await Lise Davidsen in the years to come.

Experiencing Lise Davidsen in Wagner is a major event—and especially here in our small pond, the boundaries of which she has long surpassed. She is, to say the least, a unique phenomenon who thrills opera lovers on the world's greatest stages. In just a few years, she has conquered Bayreuth Festival, the Metropolitan Opera, the Vienna State Opera, La Scala, the Bavarian State Opera, Covent Garden, and Glyndebourne. She is undoubtedly the biggest name in the opera world today; she plays in a league of her own, to use the Metropolitan Opera director's words. Now Isolde and Brünnhilde are next. Let us hope we get to see her in these roles here in Norway.

In Lise Davidsen’s interpretation, Senta is not a naive girl. When Senta sings “Ich bin ein Kind und weiss nicht, was ich singe!” Lise Davidsen clearly conveys an ironic distance with her eyes. And when Erik whines and asks if she is not moved by his suffering, she promptly puts him in his place and tells him to stop boasting about sufferings that cannot be compared to the Dutchman’s. Lise Davidsen uses her vocal power and impressive range to portray a stronger and more powerful Senta than we usually see. Her silver-toned voice can leave anyone awestruck. It is shockingly beautiful and impressive.

My greatest Lise Davidsen moments in these concerts were not the powerful outbursts in the high notes but the introduction to the ballad (“Joho hoe”), which she sang piano as written in the score (something very few Sentas do). It was beautiful, eerie, and effective. It presented a female figure emerging from the cocoon and asserting her independence. At the same time, it is Senta’s way of capturing the attention of the spinning women—and Lise Davidsen’s way of capturing the awe-struck audience. Senta’s expressed goal is to move others with the Dutchman’s fate. These four bars are dramatically contrasted with the final “Jo-hoe” in forte and then the story of the Dutchman’s fate, which begins with “Traft ihr das Schiff im Meere an, blutrot die Segel, schwarz der Mast?”, where Lise Davidsen’s vocal prowess truly shines. As the ballad progresses, Lise Davidsen builds an increasingly clear picture of an independent individual, a strong and determined woman willing to face death for what she believes in—a sharp contrast to the other women in the drama—and the views on women in the mid-19th century. With subtle, suggestive facial expressions, unmatched vocal control, and a nuanced delivery, Lise Davidsen’s Senta is neither dreamily naive, virginally innocent, insane (Kupfer), nor rebellious (Tcherniakov). It is an interpretation that will likely be a benchmark for how we understand the character of Senta. As Courtney W. Howland points out, she has “divine power, authorized by her Christian God, to save the Dutchman and his crew from Satan’s condemnation.” It is no small feat what this woman is capable of.

Lise Davidsen’s Senta is the only one who truly understands what is really happening in the drama. Here Davidsen takes advantage of the concert format; she can give us her version of Senta, not a director’s. It takes an artist of her caliber to make such a clear stamp on how we should understand Senta.

Lise Davidsen as Senta in The Flying Dutchman, concert performance, The Norwegian National Opera. Photo: Erik Berg

If one views the Dutchman’s desire for redemption as our desire for redemption, it is tempting (almost impossible not to) to see Senta as a Christ figure, who through her sacrificial death redeems us. There are not many sopranos with the necessary power and charisma to carry such an interpretation.

The Opera’s New Music Director

Photo: Erik Berg

The concert was Edward Gardner's first performance as the Opera’s new music director. Those of us who are somewhat above average in our obsession with Wagner were curious about what he had to offer as a Wagner interpreter, especially in light of the fact that he will be the conductor when the Ring is staged on our most important opera stage in a couple of years. It was a mixed experience.

The concert began with Gardner starting the music while the audience was still applauding. This bizarre stunt served as a forewarning of what was to come. The audience was to be swept away. The music was driven forward at a breakneck pace. There was very little room for lyrical delicacy, contemplation, and dynamic range. The volume in the climaxes was actually painfully high. The musicians appeared more stressed than inspired (the mistakes were numerous, especially on Thursday). There was, of course, supposed to be a powerful impact, but Wagner does not require effects larger than those written in the score. The brass players were allowed to play as loudly as they could (or perhaps they could not play more softly?), which gave a primitive marching-band effect in some passages—to put it a bit bluntly. This is an outdated way of conducting Wagner. The sound balance was often poor; I felt that the instrumental sections were playing against each other (at full strength) instead of dynamically creating a flow guided by a conductor with a vision for conveying the nuances and grandeur of Wagner’s music.

The choir also bore the mark of an insistence on singing loudly at all costs, losing the ability to bring out many nuances. The choir often appeared as a wall of high volume.

On the forthcoming CD, my objections may possibly be resolved through the producer’s work at the mixing board.

Senta! Willst du mich verderben?

There are great stakes in the relationship between the Dutchman and Senta. A person (or rather: humanity) is to be saved. In this context, the other characters in the drama become relatively peripheral.

First, we have the hunter Erik (Stanislas de Barbeyrac). What kind of guy is he, really? He is the prime example of a man that all women should avoid like the plague. Erik is probably the most irritating character in all of Wagner’s music dramas. He is extremely jealous, possessive, controlling, insistent, easily offended, whiny— a stalker who believes he has a right to Senta’s love and the right to torment her because, in his eyes, she actually wants him–she just doesn’t realize it. With unpleasant physical proximity, threatening behavior, and stalking, he tries to make her feel insecure. But Senta opposes the patriarchal culture she lives in. She is a strong woman who won’t be easily intimidated and controlled by the men around her.

Stanislas de Barbeyrac delivered a stellar performance as Erik. Photo: Erik Berg

That Stanislas de Barbeyrac managed to make me forget how manipulative and whiny Erik is, is no small achievement. Despite the conventional and banal music for this role, de Barbeyrac convinced with genuine emotions and a heartbreakingly beautiful voice. I believe his Erik must be the most beautiful I have ever heard. Genuine and authentic. Paradoxically. A person with genuine feelings beneath the rhetorical, polished surface. The banal cavatina in the third act exposes how shallow Erik is compared to Senta’s depth. Yet, de Barbeyrac manages to seduce me to the point where, for a brief moment, I forget how dangerous such jealous men can be for women. I like it. And it’s unsettling.

Daland and the Steuermann

Daland, Senta's father, is a peculiar figure. He is the village's quintessential greedy merchant, so obsessed with wealth that he's willing to sell his daughter to the first man he meets. His character embodies the stereotype of a ruthless businessman who prioritizes financial gain over moral values. Senta is his great pride, his “comfort in adversity.” He does not understand that Senta has higher ambitions than the life he has planned for her.

Brindley Sherratt's interpretation was a mix between an unsympathetic and ruthless businessman and a bumbling man who does not quite grasp what is happening. Daland does not comprehend the extent of what is at stake. Unfortunately, Sherratt was not in his best form. Despite a strong stage presence, a warm and lovely tone in the lower registers, and some fine details, his performance was not entirely satisfactory. His voice had acquired a “dry” tone on these concert days and was very strained in the higher range.

Eirik Grøtvedt as the melancholic Steuermann. Photo: Erik Berg

More satisfactory was the Steuermann, sung by the Opera’s own Eirik Grøtvedt. More melancholic than usual for this role, but Grøtvedt sang beautifully, and his voice resonated well in the hall. I sensed a perfect David in spe (Meistersinger), a role I hope Grøtvedt will have the chance to try.

Two years ago, Anna Kissjudit achieved great success as Erda in the Tcherniakov Ring at Staatsoper in Berlin; she will also sing Erda in the Schwarz Ring in Bayreuth next year. She has a very distinctive, warm, and mature voice. Her Mary was strict and authoritative but also unorthodoxly playful. A pleasant acquaintance that we would gladly experience again when the Ring is staged in Oslo.

Recommended reading

|

|

|

|