Stefan Herheim's production of Parsifal in Bayreuth

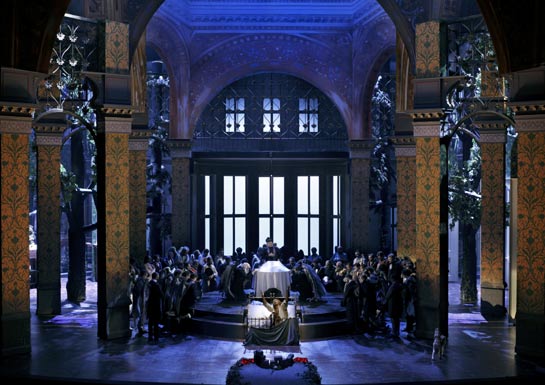

Is it a dream or is it reality? Who is the Grail? Who is Parsifal? Weisst du was du sahst? Photo: Enrico Nawrath/Bayreuther Festspiele

Premiere: 25 July 2008. Also played 3, 6, 10*, 16, 28 August.

Conductor Daniele Gatti

Production Stefan Herheim

Stage design Heike Scheele

Costumes Gesine Völlm

Dramaturgy Alexander Meier-Dörzenbach

Amfortas Detlef Roth

Titurel Diógenes Randes

Gurnemanz Kwangchul Youn

Parsifal Christopher Ventris

Klingsor Thomas Jesatko

Kundry Mihoko Fujimura

1. Gralsritter Arnold Bezuyen

2. Gralsritter Friedemann Röhlig

1. Knappe Julia Borchert

2. Knappe Ulrike Helzel

3. Knappe Clemens Bieber

4. Knappe Timothy Oliver

Klingsors Zaubermädchen (Flower Maidens) Julia Borchert, Martina

Rüping,

Carola Guber, Anna Korondi, Jutta Maria Böhnert, Ulrike Helzel Atala

Schöck

Altsolo Simone Schröder

Stuntman Matthias Schendel

Parsifal at Bayreuth, 6 August 2008

Stefan Herheim and his team consisting of Heike Scheele (stage design), Gesine Völlm (costumes) and Alexander Meier-Dörzenbach (dramaturgy) has created a multi-layered, ambiguous, interesting and very beautiful production of Parsifal. They succeed in creating a veritable dream world on stage.

The production mixes irony with sincerity and kitsch with heartbreaking tragedy, and the end result is an overwhelming emotional experience.

Narrative lines

Herheim refuses to paint the story and the characters in black and white. He doesn't even serve us one coherent interpretation. Instead we get at least three narrative lines:

- Parsifal's development as a child and later young man

- the history of Germany from 1870 to the 1950's

- the history of the Bayreuth Festival in the same period

The garden of Richard Wagner's house Villa Wahnfried was used with great effect. This photo is from Act 1. The rollover image shows Villa Wahnfried anno 2008. Photo: Enrico Nawrath/Bayreuther Festspiele

If Herheim had wanted to make a more traditional production, he would have chosen one of the story lines and developed it to a rounded whole. Instead the production points in "all" directions. This is not a weakness, but a strength.

Thomas Jesatko as a transvestite Klingsor in Act 2. His Zauberschloss is a hospital, and the Flowermaidens are nurses. Replacing some of the flowermaidens is definitely necessary for next year. Photo: Enrico Nawrath/Bayreuther Festspiele

In doing so, he is true to the abyss of anxiety, doubt, desperation and longing (both for love and for redemption!) found in the music. The redemption that we are offered in this production is filled with irony and doubt.

The basis for Herheim's interpretation is his apparent musicality. Right from the instrumental prelude, where the actors are mutely playing out Herzeleide's death, the action on stage corresponds deeply with the musical flow – often with great emotional impact. In Bayreuth I think only Harry Kupfer has been close to Herheim in this respect, maybe also Patrice Chéreau. This correspondance creates both parallels and contrasts between the action and the music (for instance with the ironic circus lights that are turned on when Parsifal sings "Wie dünkt mich doch die Aue heut’ so schön!").

Kundry with wounded soldiers. Klingsor in the background. Act 2. Photo: Enrico Nawrath/Bayreuther Festspiele

Play with identities

Herheim enters a dialogue with the work, opening it up, creating doubt, as well as new questions, and a fascinating play with identities. Instead of answers, Herheim raises several new questions for every one he answers.

In Herheim's vision personal identities are not fixed and closed once and for all. Instead their floating borders create uncertainty, doubt, and ambiguity:

- Kundry is transformed to Herzeleide and vice versa, and then to a servant who is expelled right after Parsifal is born (his birth is shown on stage), suggestive of German antisemitism

- Herzeleide wakes up from the dead and appears as a seducer (Kundry) luring the boy Parsifal into her bed

- Kundry appears as Klingsor at the end of Act 2 and like Amfortas in Act 3.

- Parsifal is present both as a boy, a man and a grotesque figure with the face of an old man. His identity also floats into Amfortas’s and Kundry’s

- The Grail is both a goblet and also the newborn Parsifal carried around to sanctify everyone around. At a certain point in Act 2, even Kundry may be presented as the grail ("Parsifal! Weile!")

The pantomime during the prelude

Conductor Daniele Gatti was first very sceptial about playing the preludes for open curtains. Luckily he was convinced. The pantomime playing out Herzeleide's death during the prelude of Act 1 is marked by great originality.

The pantomime follows the triptychon structure of the prelude.

![]()

We are in Villa Wahnfried. Herzeleide is lying in a bed. She is dying. She is desperately trying to make the son, Parsifal, come to her, but he is afraid and refuses. Three times he rejects Herzeleide's invitation, but eventually he is forced to come to Herzeleide's bed by the maid. Present is also the doctor and the priest.

When Parsifal runs out to play with his bough and arrow, his mother dies.

![]()

In the second part of the prelude Herzeleide's dead body is prepared by the doctor and the priest.

![]()

The third part of the prelude starts with Parsifal entering the room where his dead mother is lying. Herzeleide is transformed to Kundry with a red rose. The dead woman then starts to move. She starts trying to seduce Parsifal and make him come into the bed. This scene has (at least) three parallel scenes in this production: Herzeleide and Gamuret making love, Klingsor luring der Knabe (Parsifal) into his bed, and Kundry trying to seduce Parsifal in Act 2.

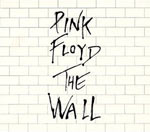

Parsifal is building a wall on Wagner's grave. The building process is also shown on a screen in the rear part of the scene. The Wall is obviously a reference to Pink Floyd's The Wall with its parallel theme of repression and the consequences of repressing. Parsifal's building of the wall is also a reference to the rebuilding of Villa Wahnfried after the war (Parsifal's wall is very much like the wall seen on post war pictures of Villa Wahnfried in ruins). There's also a reference to René Magritte's painting The Art of Conversation. There may well be more references. They are all part of the open non-didactic character of this production.

The Mirror

A very beautiful effect was the mirror that slowly descended from the roof, showing the audience as well as the orchestra and the conductor in the hidden orchestra pit. Some critics have regarded this mirror as too obvious a metaphor for the stage as a mirror, and for the rather commonplace idea that "now it is up to us to find the way". Such a one-dimensional reading, however, ignores the ironic filter established early in Act 1, forcing us to doubt every "statement" Herheim seems to be making.

The mirror showing not only the audience, but also the orchestra and the conductor, is a message from the production team: – Hey, look here, there's more in this music drama than has been seen here before – not to mention that there is something hidden and repressed concerning the past in Bayreuth and in Germany. Herheim and his team make us see something we were not meant to see. Wagner and Bayreuth have tried to hide it, but now is the time to open up.

Sleep, rest, death

Sleep is a recurring motif. Associated with sleep is death. Sleep and death is the opposite of pain (Amfortas) and restless wandering (Kundry). Amfortas is "schlaflos von starkem Bresten" (sleepless caused by great pain) and Kundry was found by Titurel as he built the castle of Monsalvat "schlafend hier im Waldgestrüpp, erstarrt, leblos, wie tot" (asleep in the undergrowth, stiff, lifeless, as if dead).

Kundry's longing for death is more ambivalent than Amfortas's. She says: "Nie tu' ich Gutes; nur Ruhe will ich, nur Ruhe, ach! Der Müden. Schlafen! O, dass mich keiner wecke! Nein! Nicht schlafen! Grausen fasst mich!" (I never do good; I long only for rest, only rest, in my weariness. To sleep! O that I might never wake again! No! Not sleep! Horror seizes me!)

The sleep motif in Herheim's production is mostly associated with the bed. The bed is introduced in the prelude as a death bed.

The Swan

Parsifal's killing of a swan is a crucial event, both in his life and in the history of the Brotherhood. It triggers a process that ends with Parsifal in the role of The Redeemer (der Erlöser) replacing Amfortas as King of the Brotherhood.

As the editor of the Monsalvat web site mentions in a note to his translation, "the swan is borne away to the accompaniment of a muffled drum, as if it were a human funeral". Stefan Herheim takes the symbolic meaning of the Swan one step further – Parsifal kills himself as a child, or rather: his traumatized childhood. Instead of a swan, the little boy Parsifal is carried in. The rest is repression, building a wall, building the castle Monsalvat to guard the Grail, building Villa Wahnfried, building the Festival House.

Simultaneous presence

The swan scene is a good example of Herheim's play with time and identities.

In the scene where the swan is killed, Parsifal is present both as a young boy and as a young man. At another time he is a grotesque old man with the body of a young boy. It reminded me of Benozzo Gozzoli's Salome painting, where three events take place at the same time in the same house: Salome dancing for her father, the beheading of John the Baptist, and Salome with the head of John on a silver plate.

Time has a new meaning in Herheim's Parsifal. He takes the elements from Wagner's music and text and intensifies their meaning. This production is much more true to Wagner than any traditional production of Parsifal has been. The simultaneous action from different time periods is very effectively contrasted with the linear timeline of the history of Germany serving as a backdrop for the production.

Anti-Semitism

Right after Parsifal is born, the maid (Kundry) carries the bloody baby around like it was the grail. She is then expelled from the house. Anti-Semitism is one of the last taboos on the Wagnerian stage. The Jews were conceived as child kidnappers and were accused of drinking the blood of Christian children. The symbolism in this scene is ingenious.

Kundry is a Jewish character, being a female equivalent to the Wandering Jew (Ahasverus, der ewige Jude). She laughed at Christ hanging on the cross, and was as a result doomed to live forever, never finding salvation. Kundry's death wish is just as desperate as Amfortas's. Both see death as the only solution to end their misery. The whole drama through, Kundry wants to rest, to sleep, and her wish is fulfilled in the end when she is baptized and sinks dead (entseelt) on the ground, two solutions the anti-Semite Wagner found appropriate. Kundry has no future.

Both Katharina Wagner and Stefan Herheim has brought the German anti-Semitism to the light with their productions of Meistersinger and Parsifal. It has certainly been done before, but not in Bayreuth.

In a television documentary about the Bayreuth Festival (they showed it on a big screen in the hotel I stayed) an elderly woman talked about how she every day went up to the Festspielhaus. She had so many good memories from the time Unser Seliger Adolf (our blessed Adolf) was in charge. The reactionaries whistling during the music this summer and booing when they saw the swastikas in Act 2 are proof that the past is more present than many would like to think.

Wagner said very clearly in Judaism in Music that the only thing that can redeem Jews from the burden of their curse is by going under, which he calls the redemption of Ahasverus. This is Kundry's destiny. In Herheim's production, though, Kundry survives as Gurnemanz's wife. The family with two children are standing facing the audience at the end of the evening.

The Wings

The characters in this production are often equipped with wings. The bird is a recurrent motif in Parsifal (swan, dove and Kundry who can fly). The wings suggest the dream nature of this Parsifal.

Is the whole story a dream or is it real?

The wings also suggests that this Parsifal production is about the history of Germany (the eagle being the central figure in Germany's coat of arms). Are the winged persons on stage good or evil? Why are the wings black or grey? Are they death angels? Again, there are no simple answers. And if you are convinced that you have the "right" answer, this probably tells more about you than about the production.

Be Aware of der Erlöser

If there is one thing this production warns us about, it is the saviours who think they have the solutions and the answers.

When Parsifal enters the Bundestag as der Erlöser, he is a hippie, totally ill-placed. This guy may think he is offering redemption, but obviously no-one believes him. The redemption has a bitter taste to it. No one could tell how the future would be with this guy as a Führer for the Brotherhood and for Germany.

The Bed

The destroyed bed in Act 3. Christopher Ventris (Parsifal), Mihoko Fujimura (Kundry) and Kwangchul Youn (Gurnemanz). Photo: Enrico Nawrath/Bayreuther Festspiele

Although the three acts are very different in style and atmosphere, there are certain visual elements binding the acts together. Most important is the bed.

In this bed…

- Herzeleide dies during the prelude in a moving pantomime (with brilliant acting from both Herzeleide and the boy)

- Herzeleide/Kundry seduces Parsifal as a boy in a disturbing scene

- Klingsor seduces Parsifal as a boy in a very disturbing scene

- Parsifal is conceived (yes, Gamuret, Parsifal's father, actually appears!)

The bed has been destroyed in Act 3, thus leaving us bewildered: Can the cycle of birth-death-rebirth continue when this central element is destroyed?

Homage to Götz Friedrich

In this production, Stefan Herheim has included an homage to his former teacher Götz Friedrich by quoting the alleged, once so scandalous ‘working class procession’ from Friedrich’s 1972–78 Bayreuth Tannhäuser (now released on DVD). A procession of exhausted cleaning women enter the stage and are included to take part in the “Wirtschaftswunder” that appeared in Germany after World War 2.

Great teamwork

Before I went to Bayreuth, I thought that this kind of production would benefit from a fast reading of the score, but Daniele Gatti proved that wrong. Gatti's slow tempi added great tension to the dream world we were witnessing on the stage.

Detlef Roth (Amfortas) and Kwangchul Youn (Gurnemanz) were both outstanding. Christopher Ventris started a bit anonymously but worked himself up to deliver a great Parsifal. Thomas Jesatko as Klingsor was very impressive, emphasizing more the irony and the tragedy than we are used to from this villain. Mihoko Fujimura as Kundry acted her part very good, and if we overlook some problems with the high notes, her beautiful, almost sinister voice suited the production well. The singer-actors acted as a team, not as individual stars. And that kind of teamwork is what we want to see in Bayreuth in the future.

The Stage a Breathing, Living Organism

The technical complexity of the stage machinery is breathtaking. Walls appear and disappear, making the stage a breathing, living organism. The ever changing sets correspond to one of the main ideas of this production, namely that ideas and identities are constantly changing (not always for the better, as the history of Germany has shown), and that stagnation, moralism, absolutism is dangerous. Redeemers with static solutions should be avoided.

What really makes this production great is the abundance of energy that went into its creation. The singer-actors, the conductor, the stage crew, the costume department and all the other involved seem to have been genuinely eager to create something out of the ordinary.

Enthüllet den Gral! Photo: Enrico Nawrath/Bayreuther Festspiele

Act 3 takes place in the ruins after World War 2. Photo: Enrico Nawrath/Bayreuther Festspiele

Stefan Herheim: Parsifal - Selected Reviews and Comments

- Abendzeitung

- Agence-France Presse

- Associated Press (2009): More impressive is the thread Herheim weaves — a century of German history replete with back-projected footage of the two world wars, smoking ruins left by the fall of the Third Reich, on-stage depictions of war wounded, fleeing Jews and — toward the end — Germany as a phoenix rising from the ashes. The links are clear but effective. Sin begets misery in the knight-priest kingdom, and pulls the country into the vortex of destruction that ends only with the redemption wrought by Parsifal. Old and new are joined, and the result is an opera that is true to its roots but relates as well on the contemporary level.

- Bayreischer Rundfunk (audio)

- Berliner Zeitung

- Bloomberg: The richness and psychological depth of Herheim's images and the seamless musicality with which he and his team have knitted them together add up to an evening of breathtaking impact.

- Boulezian blog: Daniele Gatti’s reading of the score rarely drew attention to itself but contributed to the unfolding dramas in exemplary fashion. […] The richness of the Bayreuth orchestra was ever apparent, but never more so than when it finally had our full attention, during the unstaged Prelude to Act III. That evocation of hard-won passing of time can rarely have seemed more apt than in the circumstances of this production. The gradual unfolding of the score’s phrases and paragraphs was faultless. Each act was possessed both of its own character and of an array of variegation and cross-reference. And the bells sounded better than I can recall hearing them anywhere (except of course on the most venerable of old Bayreuth recordings).

- Graham Bruce (The Wagner Society in Queensland): Herheim conceived PARSIFAL as a child's dream, with all of the Freudian implications that suggests. Now if that description suggests that this was yet another production which rode rough-shod over the text and music, I must assure my readers that conceptually, visually and musically, this was an outstanding success; indeed it's been some time since goose-bumps arose on my skin as they did during this performance.

- Corriere della Sera

- Crescendo

- Le Figaro: Un Parsifal politiquement correct

- Financial Times: The performance works on so many levels that you emerge challenged and stimulated: Bayreuth at its best.

- Frankfurter Allgemeine

- The Guardian: Herheim's production continually poses the direct question of whether Wagner's own Bayreuth legacy - like the decaying world of the Grail knights in Parsifal - can ever be morally cleansed. In pursuit of an answer, Herheim takes us on a formidably ambitious journey through a dazzlingly inventive theatrical deconstruction of Parsifal, of German history, of Wagner and, above all, of the way they are woven together in Bayreuth itself.

- International Herald Tribune: The staging is grandiose, visually sensual, and scenically enthralling. The audience's attention rarely waned during the seven-hour performance, despite the slow, deliberate pace of the score as conducted by Italian Daniele Gatti. […] Herheim makes use of every modern stage technique available to him, deploying an endless succession of technological fireworks and visual provocations.

- Kurier

- Merkur-Online

- Mostly Opera: […] myriads of ideas, sufficient for several new Parsifal productions on an over-stuffed stage, downstaging both singers and music and ultimately creating confusion as opposed to enlightenment.

- New York Times: In the end, it is moving. Directors get away with half-baked ingenuities because opera plots already require suspended judgment — and because of the music. Under Daniele Gatti’s baton, the score unwinds in grave and luxurious fashion. The Bayreuth chorus is peerless, as always. Christopher Ventris, as an ardent Parsifal; Detlef Roth, the touching Amfortas; and Kwangchul Youn, a brooding Gurnemanz, make for unexpected stars. Mihoko Fujimura, notwithstanding the straining in her upper reaches, is the desperate, heartbreaking Kundry. If someone at Bayreuth could sift through Mr. Herheim’s bounty of ideas, this might yet become a great production.

- rp-online.de

- Der Spiegel

- The Stage (Penelope Turing: Herheim is tempted by adding some ‘ideas’, but emerges triumphant because this is simply a great musical performance.)

- Der Standard

- Süddeutsche Zeitung

- Tagesspiegel

- Telegraph (Rupert Christiansen, 2009): I caught the first revival of the Norwegian director Stefan Herheim's production of Parsifal. Its first two acts are among the most beautiful and complex things that I have ever seen on a stage, and I can scarcely describe their import. [...] What further distinguishes Herheim's direction is its exquisitely sensitive musicality. The endlessly shifting and meticulously choreographed imagery flows in and out of the river of Wagner's score, as it progresses from the Bismarck era to Adenauer's reconstruction, through two world wars and the Weimar Republic, showing idealism turning to militarism and religious belief to political fanaticism.

- The Wagner Journal (Barry Millington): This is one of the finest stagings of the work ever seen at Bayreuth, or anywhere else. While undeniably complex, the dramaturgy is strong, clear and focused. The stagecraft, moreover, is superb. (Review available in the printed edition.)

- Die Welt

- Westdutsche Allgemeine Zeitung: Herheims Parsifal ist vielschichtig, aber dabei nicht beliebig. Er hält eine kluge Balance zwischen Dokumentation und Traumkosmos. Und der Norweger ist ein Regisseur von großer Musikalität: Gesten und Blicke, Gänge und Verwandlungen korrespondieren punktgenau mit Wagners Musik.

- "I have noticed a tendency to the (historically) excessive since 2008 in the production on the Green Hill by Stefan Herheim, Schlingensief’s successor as director of Parsifal: as if these directors knew what wealth Wagner had left in his last opera but did not feel able to control it and make it fertile. I think we should not be too complicated, nor always think of history before and after Wagner and show it on stage. As Lars von Trier said: if we want Wagner, then Wagner is what we want." Christian Thielemann. As quoted in Christian Thielemann: My Life with Wagner (p. 249). Orion. Kindle Edition.

Scandinavian reviews

- Mystikk og begjær. Av Erling E. Guldbrandsen

- Drømmen om forløsning. Av Ståle Wikshåland

Scene workers preparing the sets for the Parsifal performance on 6 August 2008.

"Im Grabe leb' ich durch des Heilands Huld. Zu schwach doch bin ich, ihm zu dienen.": Richard Wagner's grave in the garden of Villa Wahnfried.

Parsifal: Articles and Reviews

William Kinderman: Wagner’s Parsifal (Review and comments by Germán A. Bravo-Casas)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2017: Parsifal

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2016: Parsifal

Mark Berry: Bayreuth Festival: 2012: Parsifal

Mark Berry: Bayreuth Festival: 2011: Parsifal

Colin Bayliss: Parsifal and anti-Semitism

Bayreuth 2008: Stefan Herheim: Parsifal (Per-Erik Skramstad)

Jerry Floyd on Claus Guth's Parsifal production at Gran Teatre Liceu

Daniel Barenboim: Complete Wagner Operas (34 CD)